Offbeat Oregon: The curious case of Klondike Kate

Published 4:00 am Thursday, May 30, 2024

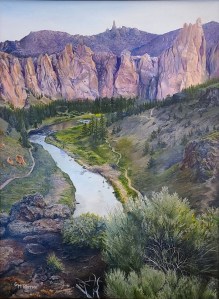

- “Klondike Kate” and an unidentified colleague pose in their costumes for a photo in Dawson, circa 1901.

Imagine this story playing out on a television or movie screen near you — or a Vaudeville stage:

Trending

Fade in on a tall, rugged-looking woman in a bright-red “Sergeant Preston of the Yukon” outfit. We hear a voiceover from a gravel-voiced narrator:

It’s June of 1901. In the Territorial capital of Whitehorse, ‘Klondike’ Kate Ryan is the first woman officer in the history of the Royal North-West Mounted Police, a precursor agency to the famous Royal Canadian Mounted Police, a.k.a. The Mounties. The Klondike Gold Rush is at its height in the summer of 1901, so Klondike Kate has plenty to keep her busy. From Whitehorse to Dawson City, the Yukon Territory is crawling with unruly gold miners, or “sourdoughs” as they are called. For Klondike Kate Ryan, it’s all in a day’s work.

But then one day Klondike Kate’s supervisor suddenly calls her into the office. She wonders if she’s made a mistake or something. What could he want?

Trending

CUT TO SCENE 2

Interior of a frontier police office with rifles on the wall and a big Canadian flag in the corner. A uniformed supervisor is sitting behind a desk glaring at Klondike Kate, who looks shocked.

Supervisor: “Officer Ryan! What’s this I hear about you moonlighting as a slutty exotic dancer in variety theatres and ‘gentlemen’s clubs?’ I can’t have Vaudeville hussies on the force! What have you got to say for yourself?”

Klondike Kate: (baffled) “I don’t know what you’re talking about, sir. I can’t dance. I can’t talk. Only thing about me is the way that I perp-walk crooks up the jailhouse steps. Like that Vaudeville dancing hooker I busted for prostitution a couple months ago, for instance. What was her name … Kate something.”

Supervisor: “Well, that’s not what our sources are telling us. They say you are dancing in your underwear on the stage in front of a bunch of leering perverts and filthy sourdoughs six nights a week. Look at this filth!”

With that, the supervsior holds up a handbill that reads “Klondike Kate’s Exotic Frolics! She Dances for Your Enjoyment at The Palace Grande Theatre, Six Nights a Week!”

Klondike Kate: (Puzzled, but with dawning comprehension) “I don’t — wait a minute, the Palace Grande, that’s the dingy doggery out of which that skanky hussy Kate What’s-her-name was working when I busted her for selling her sweet favors to sourdoughs! As she was going off to serve her month of hard labor for prostitution, I remember her glaring at me and swearing she would get me back. This is her revenge — identity theft! She’s stolen my nickname to get even with me! Can there be any other explanation?”

Supervisor: “Well, yes, there can. But I’ll give you 24 hours to round up proof that this striptease tart is someone other than you. After that, you’ll be fired!”

Klondike Kate: “I’ll get that proof, sir, and save my reputation and my job. You can count on me, sir!”

CUT TO SCENE 3

Outside the front door of a grubby, disgusting looking “gentlemen’s club” in the crappy part of town. A red light hangs over the door. Klondike Kate marches up to it and yanks it open and enters.

In the gloomy, disgusting interior of the frontier “gentlemen’s club.” Klondike Kate can see her self-proclaimed namesake on the stage at one end, capering about suggestively in a state of near-total undress while a bunch of filthy, unruly sourdoughs leer and holler catcalls at her.

The dance number finishes and the curtain comes down for intermission. Klondike Kate balls up her fists and storms up to the stage and jerks the curtain aside to enter.

In the backstage area, fake Klondike Kate stands in her skimpy stage outfit. She looks startled at first, then a malicious smile touches her features.

Fake Kate: “Well, well, if it isn’t Officer Righteous herself. How do you like these apples, you holier-than-thou harridan?”

Klondike Kate: (angry, shouting) “Stop calling yourself Klondike Kate, you brazen strumpet!”

Fake Kate: (scornfully) “Forget it! That’s mny nickname now! It started as a plan to get revenge on you, but I’ve decided I like it! Now all I have to do to perfect my revenge is to move to Los Angeles, hire a Hollywood agent and get a movie made. After that, everyone will think I am the real Klondike Kate and that you are the faker! That’ll teach you!”

A crestfallen Klondike Kate turns away in righteous disgust. Then her eye falls upon a playbill tacked upon the door at Stage Left. It is emblazoned with a picture of fake Klondike Kate in her dancing suit, and the words “Klondike Kate! Six Nights a Week!” underneath. In a flash she leaps upon it, snatches it from the door and holds it aloft in triumph.

Klondike Kate: “Aha! Now that I have this, I don’t care what you do, as long as you’re not still whoring around breaking the law, you dirty little trollop. I’ve got my proof right here. With this proof that it is you and not me, the REAL Klondike Kate, twirling around in a skimpy bikini in front of dozens of lecherous sourdoughs, I will redeem my reputation and go on to a long and rewarding career in frontier law enforcement. Farewell, thou dirty dirty Vaudeville ho, thou!”

Fake Kate: “Curses! I am robbed of my revenge!”

CUT TO SCENE 6

Outside the police station. We see real Klondike Katemarching triumphantly up the street, playbill in hand, and entering the station as narrator speaks in voiceover:

“And indeed, Klondike Kate Ryan would redeem her reputation that day, and go on to a long and rewarding career as a policewoman. But the dancer would make good on her threat. Years later, after leaving the Klondike, the fake Klondike Kate would indeed hire a Hollywood agent and sell her phony story to the movie industry. As a result, today when people talk about Klondike Kate, most people think of the dancer who stole the real Klondike Kate’s nickname and got Mae West to play her on the silver screen. The real Klondike Kate, history’s first identity-theft victim, is mostly remembered only in dry history textbooks, and in the hearts and minds of the few of us who know the truth.”

FADE TO BLACK.

Great story, huh? Somebody get Netflix on the phone, this set-up is good for at least three seasons!

But, of course, the story is completely bogus. The only historically accurate parts of it are the names of the characters and the occupation of one of them — that of Officer Kate Ryan.

The “Klondike Kate Catfight” narrative has evolved over more than 100 years of tellings and retellings in movies, TV shows, and books, ever since the release of a 1915 novel titled “Ruggles of Red Gap” by Harry Leon Wilson.

Ruggles is a work of fiction that has, over the decades, managed to get merged into the true stories of two different frontier Yukon women, augmented and altered over years of creative embellishments by different storytellers.

The two women were, of course, “Klondike Kate” Ryan the frontier cop, and “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, the Vaudeville dancer (who, in most modern versions of this “Katfight” yarn, gets renamed “Kitty”).

The truth is that Kate Rockwell and Kate Ryan almost certainly didn’t even know of one another’s existence. Ryan lived and worked in Whitehorse, which was at least seven days of hard travel away from Dawson City, where Rockwell was.

Also, Kate Rockwell didn’t perform under “Klondike Kate.” She didn’t acquire that nickname until much later, in the 1920s. And it also has to be pointed out that Kate Rockwell, so far as I’ve been able to learn, was never a prostitute or sex worker.

She was, though, an Oregonian. And since 1912 she has been part of Central Oregon — both literally and figuratively.

In Part Two of this story, we’ll talk about Klondike Kate Rockwell’s story — how she became known as Klondike Kate, and how Central Oregon became the chrysalis from which she emerged as the legendary and beloved Aunt Kate of Farewell Bend.

Braly, David. “Tales from the Oregon Outback: Prineville:” American Media, 1978

Walth, Brent. “Fire at Eden’s Gate: Tom McCall and the Oregon Story,” OHS Press, 1994

McCall, Dorothy Lawson. “The Copper King’s Daughter,” Binfords, 1972.