Offbeat Oregon: “Prepaid Shanghaiing” went badly amiss when the victim unexpectedly died

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, June 19, 2019

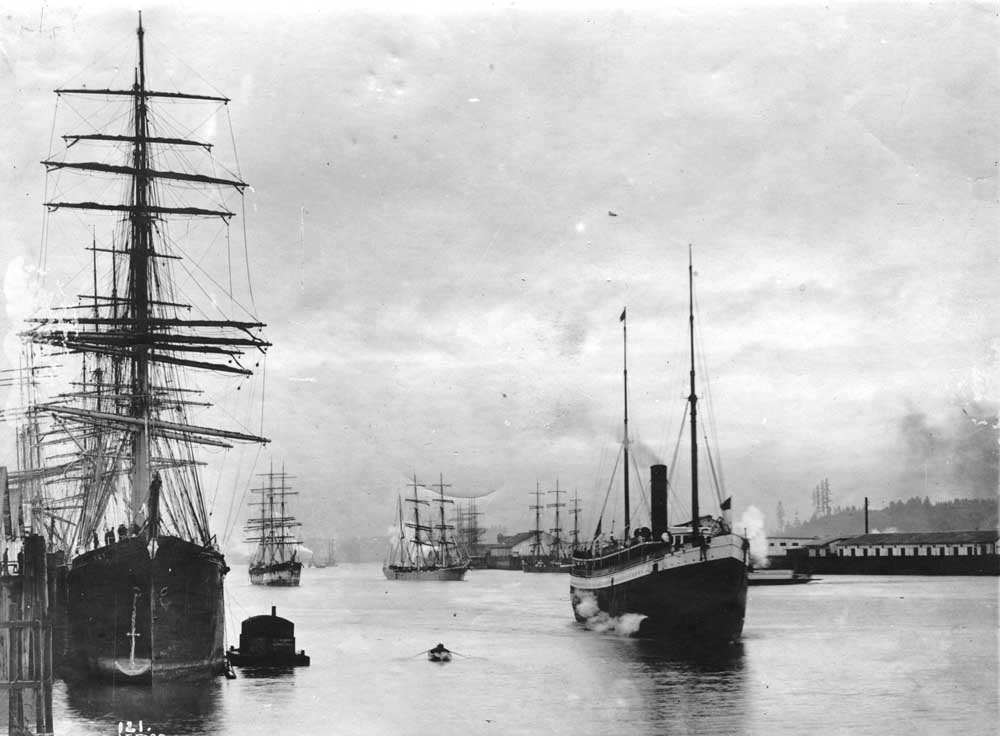

- Ships in the Portland Harbor, sometime in the late 1890s. (Submitted photo/OSU Libraries)

Most of the time, the shanghaiing of sailors in old Astoria and Portland was a spur-of-the-moment kind of thing. It was resorted to when a ship captain needed a crew for an imminent departure, and the shanghaier didn’t have enough legitimate sailors staying in his boardinghouse who could be forced to ship out.

But there was at least one sailor who arrived in Portland with his shanghaiing already planned, premeditated and paid-for. And it probably would have worked just fine if he hadn’t foiled his would-be shanghaiers by dying on them.

Frederick Kalashua was a big burly Finn, and no ordinary sailor. He was a ship’s carpenter, and apparently a pretty good one, so he was far more valuable to the captain of the ship he arrived on, the 190-foot British barque Candidate, than the average sailor would have been.

When Kalashua arrived in Portland in late June of 1886, he was angry with the captain of the Candidate, and didn’t much care who knew about it. The skipper, he said, had fed him very poorly and forced him to share a cabin with a black man. Although the captain had promised to move the roommate to other quarters and to improve the food, it seemed Kalashua was enough of a racist that having been forced to share his quarters with a black man had been an unforgivable insult. He arrived in Portland ready to quit, and when he checked into Jim Turk’s boardinghouse he immediately put his name down on the list of sailors seeking other berths.

He also asked one of the boardinghouse runners, Pat O’Brien, to go to the Candidate and get his box of carpentry tools, which were his own personal property and valued at about $250 (about $7,000 in modern money). O’Brien tried, but the captain refused to let him take the tools. He — the captain — had no intention of letting his carpenter leave his employ, and had made arrangements that he was confident would ensure that Kalashua was safely back on board when the Candidate moved on.

Those arrangements essentially amounted to a prepaid shanghaiing. The captain had deposited $60 with the British consulate, to be handed over to boarding master Turk after the Candidate cleared port with carpenter Kalashua safely on board. Turk, of course, knew this, and was making plans to earn the cash.

Unfortunately for everyone involved, he was depending on a big dumb thug named Daniel Moran to implement those plans.

On July 8, Moran went out drinking with Kalashua. As Moran knew, and maybe Kalashua did too, the Candidate was scheduled to depart at the next high tide — 3 a.m. the following morning. Moran was working to soften the big Scandinavian up a bit.

Over the course of the day, Moran would later testify, the two of them wandered the waterfront, soaking up drinks — “thirty or forty” apiece, if we can believe that. As they were making the rounds, Jim Turk asked Moran what he was doing.

“I am going to fix this fellow off,” Moran replied, according to Turk’s testimony, and resumed bar-hopping.

Near supper time, Moran decided it was time to do the deed. So he chirped, “Let’s take another drink!” and led Kalashua and several others to a nearby saloon owned by James Kelly. Unbeknownst to all, he had made arrangements with Kelly to slip Kalashua a mickey. It was about to be night-night time for the big squarehead, who would be waking up the next morning aboard the ship he so wanted to leave with the captain he so hated — or so Moran thought.

But Kalashua was feeling sick from all the booze. He staggered to the edge of the sidewalk, vomited in the gutter, and then followed Moran into Kelly’s saloon, where he declined to take a drink, asking instead for a glass of “soda water” (meaning a bicarbonate of soda, to soothe his upset stomach).

This probably was the moment things went off the rails. Moran and Kelly had made arrangements to drug Kalashua, and those arrangements almost certainly involved a bottle of whiskey laced with a carefully measured amount of opium. But Kalashua wasn’t drinking it. So instead, Kelly had to sneak and dump some opium in the bicarbonate of soda, estimating the dosage on the fly. He then added some sugar, stirred it, handed it to Kalashua, and told him to “drink it up quick.”

Kalashua did. Then he returned to the boardinghouse, stretched out on the sofa, and did not move until the death throes came.

He died a few hours later, and by that time there were three physicians on the scene, all of whom agreed he’d clearly died of an opium overdose.

Incidents like this weren’t as common in 1880s Portland as popular legends would have us think — but they weren’t exactly uncommon either. It’s debatable whether the death of some luckless hobo or laid-off logger in a shanghaiing overdose would have received much — if any — attention in the newspapers. But the involvement of the British consulate, and the status of the victim as a skilled marine craftsman, combined to give this story some legs. The ensuing trial was covered fairly extensively in the Morning Oregonian, although never on the front page.

Authorities soon had both Moran and Kelly in custody. Moran, who had a great deal of trouble keeping his hands to himself, made things easier for the cops by getting himself arrested for picking a fistfight with Pat O’Brien shortly after the doping — so he was already in the slammer when the rap came down. This gave him a leg up on what turned into a race with Kelly as each jockeyed to be the first to flip, turn state’s evidence, and squeal on the other. By the time Kelly was in custody and offering to do so, it was too late, and he was on the outside looking in.

And so, in early November, saloonkeeper James Kelly found himself in court answering a charge that was probably going to send him straight to the gallows — first-degree murder. Although the death had been an accident, because it had happened as a result of Kelly committing a felony (kidnapping) the statute called it murder one.

Things were looking extremely bleak for Kelly as the evidence was presented. It was pretty clear that he had, at Moran’s request, spiked Kalashua’s Alka-Seltzer with a fatal overdose of opium. Moran, in the full confession he’d offered in exchange for leniency, had already testified that Kelly had leaned over to him after the doping and whispered, “I think I have given him too much, but never mind, the (expletive) can stand it.”

Then came the moment when Moran was called to the witness stand, and the bailiff went to fetch him, and found his cell empty. The jailer had left him in the hall while he went to look for another witness, who — although he also was supposed to have been locked up in a cell — had stepped out for a couple of cocktails before breakfast and not returned. While the jailer was out hunting for him, Moran simply strolled out the front door.

Everyone was furious with the jailer after this, and the newspaper reporters dropped broad hints that it had been a conspiracy and the jailer was in on it. But there was not much to be done at that point. The judge ruled Moran’s confession inadmissible, and a few days later — Moran still being on the lam — the jury ruled Kelly “not guilty.”

Moran managed to stay lost for almost two whole weeks. He moved to Wallula, where he was doing a pretty good job of keeping a low profile until the temptation to get into another knock-down-drag-out bar fight became too strong for his feeble intellect to resist — at which point he was forced to leave town ahead of an angry mob. The sheriff’s detective who was out looking for Moran soon heard about it, and picked up his trail there, finally catching him in Spokane Falls. And a week or two later, Moran found himself in court, facing the same charge Kelly had just been acquitted of: Murder one.

Following a short but eventful trial, Moran was convicted of first-degree murder.

The Morning Oregonian was very happy about this.

“Moran may now take what comfort he can out of the fact that he has succeeded in saving his accomplice’s neck at the expense of his own,” editor Harvey Scott wrote in a very crisp editorial after the verdict. “This verdict was much needed. It will put a check upon the practice long prevalent here of ‘doping’ sailors, so as to facilitate the industry of crimping, kidnapping or otherwise decoying or conveying them on shipboard, so as to get their advance wages. More men than Kelly and Moran have been in this nefarious business at our Northwestern ports for years, and it is high time that some one or more of the scoundrels hanged for it.”

And hanged for it Moran certainly would have been, but for one little detail: Portland Police Chief Samuel Parrish testified that after Moran was arrested, he’d been locked away in a dark cell in solitary for three days and his repeated requests to talk to his lawyer had been ignored. The chief, who had been on the job less than two years and had no previous law enforcement experience, testified that no one had actually told him to deny the request for a lawyer, but he’d heard district attorneys grumble about suspects getting to talk to lawyers and thought this was what was expected of him.

All in all, late 1886 was not the Portland law enforcement community’s most shining moment.

Not too surprisingly, the case was overturned the minute an appeals judge learned about this. Moran was eventually convicted of manslaughter, and sent back to the pen to start a 15-year stretch for the job.

Jim Turk, the owner of the shanghaiing shop, on whose behalf all this dirty work was being done and who would have reaped the $60 reward if it had been done properly, was never charged, or even seriously questioned — despite having essentially confessed to having known about Moran’s plan to shanghai Kalashua for him.

Apparently everybody knew it wouldn’t do any good. In the Portland waterfront of 1886, the fix was always in.

(Sources: The Oregon Shanghaiers, a book by Barney Blalock, published in 2014 by The History Press; Portland Morning Oregonian archives, July–December 1886)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn2@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.