Bach wrote the book on housing in Central Oregon

Published 9:13 am Thursday, May 1, 2025

Jonathan Bach has lived in a lot of homes. His family moved often while he was growing up, including into and out of an affordable rental in east Bend, and a place they later purchased in Terrebonne.

Bach eventually moved in a dorm room, graduated from the University of Oregon and became a journalist. He currently covers housing and commercial real estate for The Oregonian in Portland.

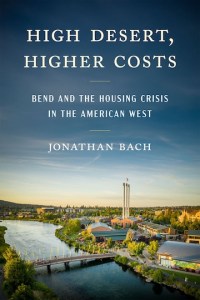

As his career took off, his family’s housing journey in Central Oregon kept his interest — especially as he noticed similar issues pulsing through many western towns. Bach knuckled down and decided to make a serious academic study of it. OSU Press supported the project and published the book that resulted from Bach’s reporting, titled “High Desert, Higher Costs: Bend and the Housing Crisis in the American West.”

You can listen to Bach discuss his work and the problems and possible solutions for housing in Central Oregon from 5-6:30 p.m. on May 17 at OSU-Cascades’ Ray Hall Atrium, 1500 Southwest Chandler Ave in Bend. The event will include a conversion with local voices from Central Oregon including Tim Trainor, Redmond Spokesman editor.

The Spokesman sent some questions to the author after reading the book. These are the author’s responses, unedited.

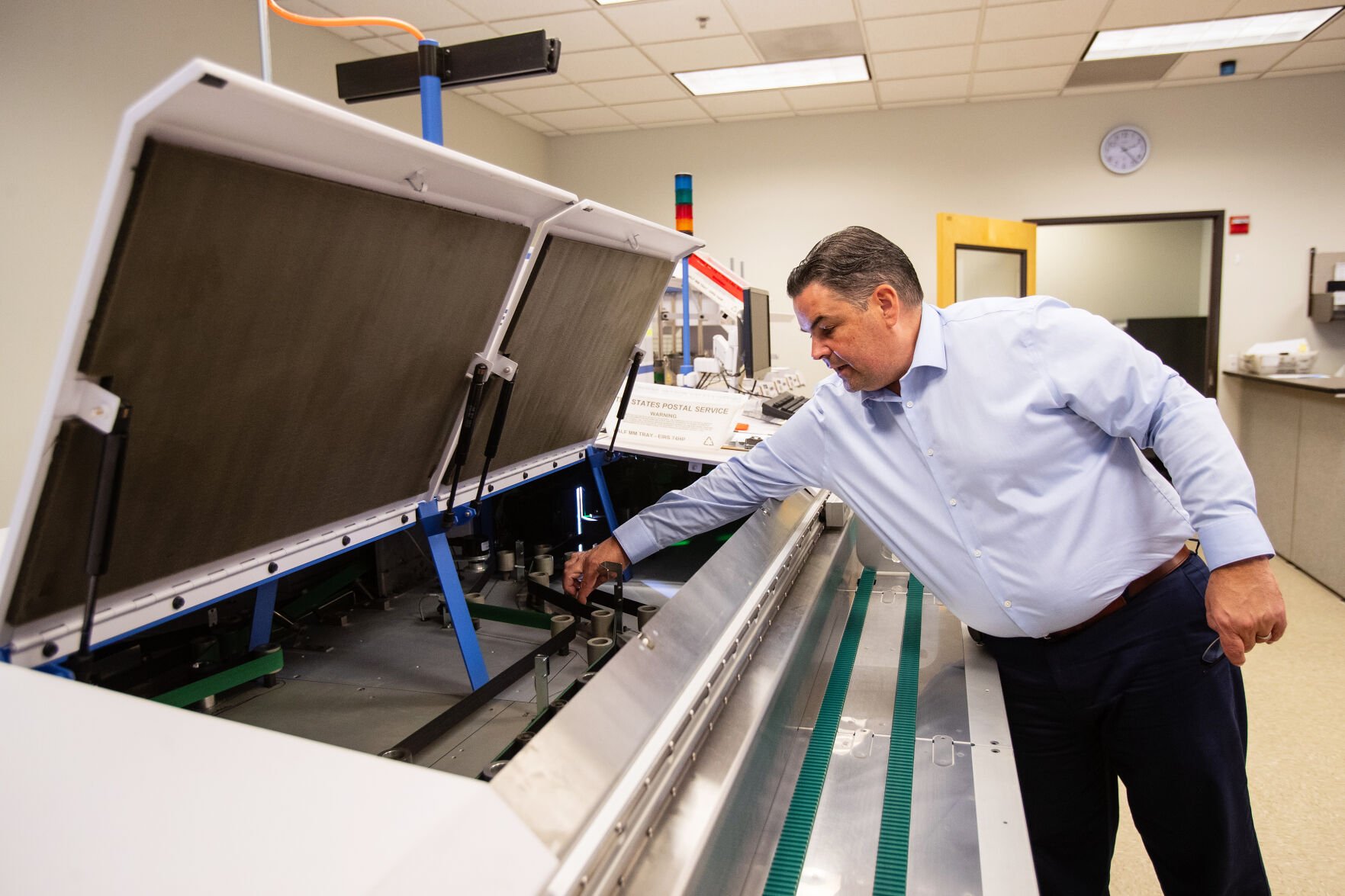

Author Jonathan Bach

Q: You moved a lot as a kid and your parents rented most of their lives. What did “home” and “a home” mean to you and your family?

Like many people who move frequently, I could rattle off a lot of the street names where we rented. But amid that blur, the constants in my childhood were my family and our Land Rover Discovery Series II, which we used to drive cross-country. I remember listening to audiobooks on cassette while my mom and I were in the SUV, and my sister and dad drove the moving truck. Being with my family was home.

Q: What makes Central Oregon unique when it comes to housing, and what characteristics does it share with other western cities dealing with their own affordability crises?

Bend and many other western cities are intensely desirable for how close they sit to natural amenities and recreation: hiking, biking, snowboarding and rock climbing. Locals want to look out their front windows and see the mountains.

Trouble is, Bend homebuilding plummeted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and was slow to bounce back, even as the city gained population. Add in a COVID-19 remote work boom, which reemphasized Bend’s popularity as a telecommuting haven, and home prices have risen beyond the reach of many families.

Q: What about the city’s founding and early days still resonates in its housing issues in 2025?

Regional histories written by the late Central Oregon Community College professor Raymond Hatton are cited extensively in High Desert, Higher Costs, because they hold a wellspring of local insights.

An example: In Hatton’s Bend in Central Oregon, he writes, “Curiously enough, one of the attractions of Bend and of Central Oregon in 1910—as it still is today—was the attempt to flee the ‘big city’ and return to the country.” Sound familiar? That was from the second edition of Hatton’s book, which published in the 1980s. Bend’s attractiveness as a destination for urban expats is not new.

What that says is, Bend will likely continue to experience population growth, which puts pressure on local and state leaders to lay the groundwork now for housing affordability into future decades.

Q: What does Bend stand to lose if the cost of living here becomes untenable for most working people?

When you can’t afford to live where you work, you might end up commuting in from farther away, which comes with all kinds of carry-on costs. One longtime Bendite I interviewed, a community organizer named Greg Delgado, was evicted from his downtown apartment during COVID-19 and launched into an expensive rental market. He ended up going to live with a friend in Terrebonne temporarily.

But Delgado, who worked at a Bend eatery, was now joining the city’s many thousand inbound commuters. So he didn’t have time to keep much of a social life.

That was a difficult period for him, he said, because his life and his other relationships were in Bend.

“Moving to Terrebonne basically just severed all of that,” Delgado said.

When people are forced to move out of town, they might not have the same incentives to spend locally or reinforce their ties within the community through civic engagement.

Q: At the same time, people who invest in a city by buying property should see that investment increase in value. Isn’t that a sign of a growing and prosperous community?

Absolutely. You don’t buy a home because you want to see your property value fall. One of the most distinct challenges today is striking a balance between the needs of longtime homeowners who rely on rising home equity as a means of wealth accumulation and the interests of prospective buyers trying to make their first purchase, so they can start building equity, too.

Q: What steps can be taken to make housing more affordable and fairer in Central Oregon?

Economists say communities like Bend need more housing in general to keep rapidly escalating rents and home values in check. Builders are looking at ways to construct more homes while also working within the bounds of Oregon’s land-use system, which was established back in the 1970s to contain urban sprawl.

But projects such as community land trusts and other nonprofit and even some for-profit models are geared toward building low- and middle-income housing, which economics firm ECONorthwest has specifically highlighted as a need in Central Oregon.

My reporting showed that directing resources toward those two segments — low- and middle-income housing — would represent a step in the direction of making Bend a more affordable place for everyday residents to thrive.