Construction workers key to Central Oregon growth

Published 9:30 am Thursday, October 31, 2024

- Miles Rosales, 21, is an AmeriCorps construction team leader for YouthBuild

Miles Rosales loves to work with his hands. He wakes up each weekday at 4:45 a.m. to drive more than an hour to the job site where he swings hammers, saws lumber and teach YouthBuild members basic construction skills.

Yet Rosales, just 21 and living in Warm Springs, isn’t sure he wants to remain in construction for long. He wonders if a career in forestry would be more fulfilling — and allow him more avenues to advance in the industry.

Rosales is not alone. Nationwide, the construction industry is seeing a reduction in the amount of workers. But in Redmond and Bend, numbers show another story.

As the region has grown, the number of construction industry jobs in Redmond and Bend also grew by 30% from 2015 to 2023. There are currently roughly 8,100 people working in the construction sector in both cities, according to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Employees

Rosales joined YouthBuild last year and graduated in June. He now works as an AmeriCorps construction team leader, where he’ll spend 1,700 hours over the next year teaching high-school aged participants construction skills and working alongside them to build affordable housing.

Rosales joined YouthBuild to learn more about the industry, though he’s still undecided if there’s something else he wants to pursue. Prior to this program, he was a part of the Central Oregon Youth Conservation Corps for three years.

“That’s where I kind of fell in love with playing with tools and working with wood and all that,” Rosales said.

Rosales said he was mainly interested in joining YouthBuild for their BOLI pre-apprenticeship program.

“It basically shows you know what you’re doing and you’re not gonna kill anybody,” he laughed. “You know, all the safety stuff.”

He said it’s better to have training under your belt, once you’re in the industry.

“I like building things,” Rosales said. “So far, I like (construction), but at the same time, there’s other stuff I could be liking, too.”

Rosales is interested in forestry and mechanics and plans to use his $6,895 YouthBuild scholarship at Central Oregon Community College to study these subjects.

“I miss going back to the woods, getting kind of lost out there, and enjoying the beauty of the forest,” he said. “Something about waking up early in the morning and going into the woods first thing, to me, that seems pretty great.”

Rosales has heard a bit about a construction worker shortage, since his father and stepbrother both work in the industry. His dad has been in construction for 10 years and his brother for seven.

“It’s not a luxury job,” Rosales said. “(My step brother) bought a truck just to sleep in it and bought the canopy over the back of his bed, so he made a little room back there so he just parks his truck at the job site and sleeps there.”

Rosales commutes from Warm Springs. He hits the road after inspecting his truck, “bumps some tunes” and picks up the rest of his crew. He said he likes the long drives to relax before starting his day.

Rosales said the heat and hard labor are driving factors for people to leave the industry, as well as on-the-job dangers. A worker must remain alert at all times, which is why most construction companies drug test their employees upon hiring and throughout their time working.

Dylan Benford, 27, agrees that the work is “daunting” enough that it may keep people from the industry. He’s worked at SunWest Builders for almost three years.

“I mean you can go work at McDonald’s or something for almost the same amount of money starting out, why not just flip burgers instead of carrying boxes around all day?” Benford said.

According to ZipRecruiter, the average wage for Bend construction workers is $26 an hour. McDonalds employees make around $21 an hour on average, according to Indeed.

Benford went into construction because, like Rosales, he too likes working with his hands. His friend mentioned SunWest was hiring and after putting in an online application, he heard back in a week. After interviewing and onboarding, Benford started working about three weeks after he first applied.

“It was surprisingly simple,” Benford said.

Benford said the majority of his coworkers have worked at SunWest for five or more years. He said there’s some “20 year veterans” as well, though not many of them.

As of January, the median time an U.S. employee stayed at a construction job was 3.9 years, said Andrew Grimoldby, Oregon Employment Department economist.

Benford said a reason why people may leave the industry lies with the work environment.

“In my personal experience, it’s not necessarily the work itself that drives people off, it’s the other people,” Benford said. “They might not mesh well, their personalities and attitudes don’t quite line up and there’s a bit of friction in that sense.”

During his time at SunWest, Benford said that team communication — and communication between companies — has improved. Part of that, he said, his maturing himself.

“It’s a big thing, just learning how the people I work with communicate and getting used to them as people,” he said.

Employers

Though relatively stable now, construction management have expressed concern about older employees heading off into retirement and not enough younger workers signing up to take their place.

“There was an intensive push towards not post-secondary, but college specifically, and when that shift happened, kids were really pushed away from the building trades, manufacturing, those kinds of jobs,” said Heather Ficht, the executive director of East Cascades Works.

Ficht said that new employees can’t afford to pay for apprenticeship trainings, leading some to get stuck in low-paying, menial jobs and then leaving the industry for better options.

“We’re really needing to think differently about how we educate folks because we’re finding we’re needing to give people a stipend to participate in training that we pay for because they can’t afford it,” Ficht said.

In an effort to provide job training to high school students, Heart of Oregon Corps’ YouthBuild introduces teenagers and young adults into the construction industry. They also help youth earn their GED, high school diploma or college credits, and get them started toward pre-apprenticeship training and credentials from the National Center for Construction Education and Research.

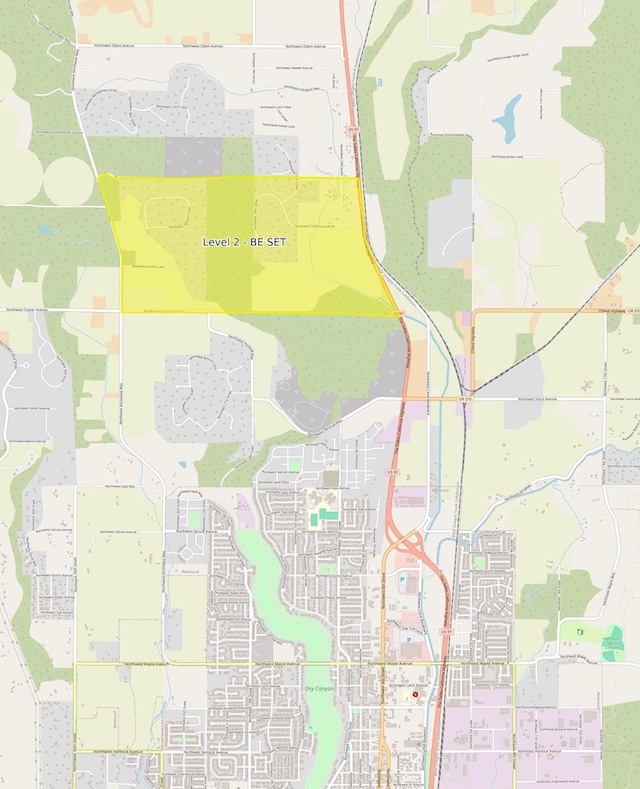

At Central Oregon YouthBuild, students come from Madras, Warm Springs, Prineville, Sisters and Redmond. YouthBuild’s campus is located between Sisters and Redmond.

“A lot of our youth are low income, a lot of them are struggling in school … We serve a lot of disadvantaged youth here in Central Oregon,” said Heart of Oregon Corps’ Deputy Director Kara Johnson.

Johnson said the organization works to stabilize the lives of teens who are considering dropping out, or are not on track to graduate. Most members register when they’re 17 years old, but the program takes students aged 16 through 24. YouthBuild offers transportation if needed and supplies them with things needed to be productive, like an alarm clock.

After completing YouthBuild, Johnson’s team works to place youth in career placement and transition. They offer scholarships and compensation for a year of work and another year of follow-up services.

Not all youth continue in the industry, but YouthBuild provides them work experience to jumpstart their careers. About 60% of their youth go into the construction industry after completing the program, Johnson said.

However, there are a few factors and barriers for why someone may not continue.

“The drug policy, that’s the biggest shock,” Johnson said. “They’ve lost a $20 an hour starting job because they can’t pass the drug test.”

YouthBuild works with youth to get them drug and alcohol free, offering a health class and referring those that need it to treatment centers.

“It’s a barrier for young people coming in and they just don’t understand it or it’s their coping mechanism of dealing with trauma,” Johnson said, adding they do counseling referrals as well.

The legalization of marijuana in Oregon is affecting job placement of younger workers, Ficht said.

Additionally, other barriers include women straying away from the industry due to stereotypes and harassment. Reliable transportation is also needed to commute to job sites, which can be a financial burden to some.

“You absolutely, fundamentally, have to have a driver’s license,” Ficht said.

Other than just finding people to hire, SunWest Builders Employee Relations Manager Crystal Henderson said it’s a struggle to find long-term employees.

Henderson said out of their 55 staff members, only 16 have worked at the company for over 11 years.

“Our turnover rate is not super high, but we do take a lot more time in screening our employees because we’re really looking for a long-term individual that wants to stay in Central Oregon and really desires to be in the trade they’re looking for,” she said.

The average age of SunWest workers is around 40 or 50, Benford said.

Henderson is chair of Oregon Carpenters Joint Apprenticeship and Training Committee. They started an apprenticeship program when she noticed how hard it was to find employees for SunWest.

Additionally, Henderson partnered with CCOC and Tillamook Bay Community College to clear the pathway for those seeking construction employment, which included Benford. SunWest paid for him to go to TBCC and learn carpentry.