Offbeat Oregon: Wall Street hustler bet on Prineville and won big

Published 4:00 am Thursday, May 16, 2024

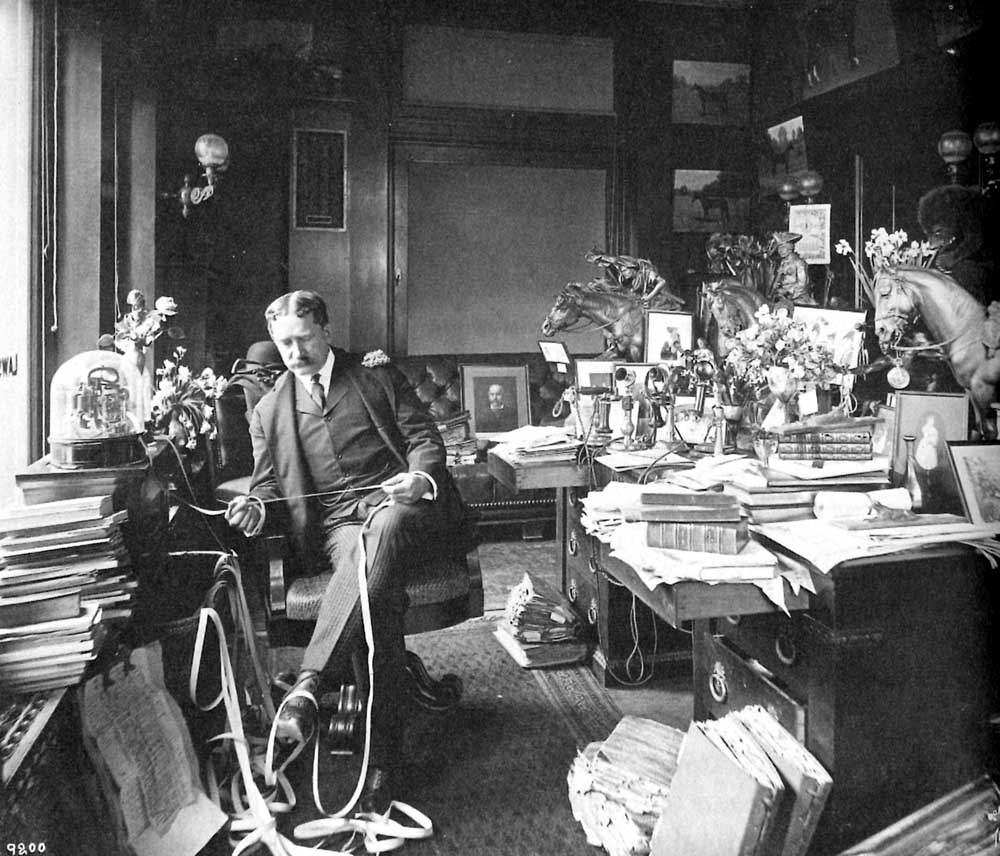

- Stock promoter Thomas Lawson reads ticker tape in his office on State Street in Boston, probably in the mid-1890s. The photograph on his couch is of J.P. Morgan.

It was the summer of 1910 and Prineville’s local baseball club was feeling hard-pressed as they left the field for the seventh-inning stretch. They were down 9 to 0 against the visiting team.

Trending

The game they were losing so badly was the third in a best-of-three tournament that pitted Prineville against the Silver Lake team. The two towns were a fairly even match in terms of population. Their two baseball teams had developed a friendly rivalry of the Ducks/Beavers kind.

In this tournament, Prineville was playing host and Silver Lake had been invited to bring its best and brightest, its fastest-running and its hardest-hitting, with the all-important bragging rights at stake.

But after the first game ended in an unexpectedly brutal loss at the hands of the visitors, the Prineville fans figured out the truth: Silver Lake boosters had gone to Portland and hired some professional ringers for the occasion.

Trending

This wasn’t cheating exactly. Nobody had said they couldn’t hire mercenaries to take their place on the field of battle. It just hadn’t occurred to the Prineville ballers as a possibility.

Obviously, though, it had occurred to someone. The team that was taking the field against Prineville, sporting Silver Lake colors, was mostly made up of guys from other places — guys who paid the bills swatting baseballs around and running bases, or performing similar athletic feats. Prineville’s motley collection of amateurs — cowboys and shopkeepers who played ball on the weekends for fun and to keep in shape — didn’t have a chance against these pros.

So after that awful first-game loss, a pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game — in the Prineville benches at least.

In the second game, Prineville managed to rally and squeak out a win. Doubtless Silver Lake’s horde of hirelings allowed this on purpose because they wanted to be paid for three games rather than two. But, a win was a win. The series was now tied at one win each. The winner of the third game would clinch the trophy.

Most of the way through the third game, there was little doubt as to who that winner would be, and upon Prineville’s stricken multitude grim melancholy sat (sorry about that. OK, I’ll stop now). But in my defense, the scene certainly seemed like it was right out of “Casey at the Bat.” Silver Lake had “torn the cover off the ball” on practically every at-bat, and put nine unanswered runs across home plate. Now all they had to do was coast through the last two and a half innings without giving up more than eight. The pathetic, scoreless Prineville team was ready to have a fork stuck in it. It was as good as done.

Or was it?

Well, see, that was the thing. There was a stranger in town just then, a visitor from back East. A dapper, well-built gentleman of about 50 in an expensive, well-tailored suit with a wallet fat enough to pull $1,000 out of and bet it all on Prineville. Which, of course, he had promptly done.

His name was Thomas William Lawson, and he had made his considerable fortune speculating on copper mines on Wall Street. Today he was hoping to augment that fortune a little more by speculating on the outcome of the Prineville-Silver Lake tournament.

Like all professional gamblers, Lawson was OK with losing his stake. But he would very much prefer not to. And he had a plan in mind for putting the odds a little more in Prineville’s favor.

A famous gambler

Thomas Lawson was a somewhat famous man — famous, and infamous to boot. He was, essentially, a reformed Wall Street shark.

Born into a solid, respectable lower-middle-class family as the son of a Massachusetts carpenter, Lawson ran away from home when he was 12 and got a job as a bank clerk. There he saved up his salary and used it to speculate on the Boston stock market, specializing in copper-mine shares. That would have been around 1870, so it was already becoming clear to those who were paying attention that copper would be the most important strategic metal of the age — essential for all the new technologies: electric motors, telegraph services, undersea cables, etc.

Lawson made sure he understood all about copper, copper mining, and the use of copper in industry. With that knowledge, he parlayed his scanty holdings into a pretty solid position over the following couple decades. Then, when the copper boom of the 1890s hit, he was ready to go. Within a year or two he was a multi-millionaire.

The 1890s were very good to Lawson, in spite of the depression that broke out in 1893. But then, in 1899, he went a little too far. He became the point man, the public-relations face, of the gang of financial thugs responsible for the Amalgamated Copper incident — which was quite possibly the most notorious stock-market swindle of the Gilded Age. (If the name “Thomas Lawson” has been striking you as oddly familiar for some reason that you can’t quite put your finger on, this may be why.)

Amalgamated con

For the Amalgamated Copper job, Lawson teamed up with notorious robber-baron plutocrats William Rockefeller and Henry Rogers. The three of them formed an empty shell company called Amalgamated Copper and, through it, bought an option to buy Anaconda Copper for $37 million. Then they set about whipping up a public feeding frenzy over shares in Amalgamated — which was still just an empty shell — by representing the deal with Anaconda as already complete. The idea was to use the proceeds of the feeding frenzy to exercise the option.

That feeding frenzy was Lawson’s contribution to the project. Unlike Rogers and Rockefeller, he had a good reputation as a whip-smart man and a straight shooter — or what passed for a straight shooter on Wall Street at the time. People did not trust Rogers or Rockefeller, but they trusted Lawson. So when he urged them to buy as many shares as they could, they did.

This probably would have worked out great for everyone involved, but as shares in Amalgamated Copper rocketed north of $175 a share, someone — probably Rogers or Rockefeller — realized that the stage was now perfectly set for a pump-and-dump operation of historic proportions. So before the deal was complete — when Amalgamated was still just a shell with no assets beyond that one purchase option — they leaked the word that Amalgamated didn’t really own Anaconda yet, and that there was no reason why it might not just close down and keep all the money it had raised rather than exercising its option to buy it.

The result was catastrophe for all the smaller investors who had poured their money into Amalgamated. Shares plunged to below $30. Investors who were able to hang on and ride the storm out were OK, but many investors weren’t in a position to do that, because they’d borrowed money to increase their position.

Many of them had done that because Lawson had been promoting it as a fabulous opportunity. He’d been telling everyone he knew, for weeks, that Amalgamated was the best, most sure-thing investment opportunity he’d ever seen. “Go your limit!” he’d urged, flat-out. And boy, they did.

Thus, Lawson had been in charge of the “pump” part. Did he know about the plans for the “dump?” He claimed not to, and those claims do ring true. His reputation was thoroughly burned in the fiasco. Nobody in the investment community would ever trust him again. The considerable wad he earned by following his own advice and “going his limit” buying on the “dump” dip would be the last money he’d make on Wall Street, or close to it.

It was quite a swan song, though. It pushed his net worth over the $50 million mark (worth about $1.9 billion in 2024 dollars).

Lawson clearly felt the pump-and-dump leak as a betrayal, especially as numerous small investors who he knew personally and had thought of him as a friend were ruined after borrowing heavily to buy shares. Several investors were reported to have killed themselves over it.

Haunted by feelings of guilt over his part in this big deed of villainy, Lawson withdrew from Wall Street and, essentially, retired. He was in his early 40s at the time.

A few years later, in 1904, he tried to redeem himself by writing a confession of sorts — a tell-all titled “Frenzied Finance,” which ran as a serial for two solid years in Everybody’s Magazine. It sold magazines like you wouldn’t believe, and had a noticeable impact on public pressure to crack down on trusts.

This pressure made Henry Rogers and William Rockefeller hate Lawson as much as he already hated them. But that suited him just fine. He’d made enough money to never have to work with them, or crooks like them, ever again. He settled into life as a 45-year-old retiree, on the thousand-acre grounds of his magnificent mansion next door to the Kennedy estate.

Out west

So now, about five years later, Thomas Lawson was in Prineville, watching the baseball team he’d bet heavy money on getting trounced.

What was a guy like Lawson doing in Prineville, anyway? Actually, he was there to buy a nice country estate to give his daughter, Dorothy, and son-in-law, Hal, as a wedding present. He had just happened to be in town with Dorothy and Hal the day of the game, and they had just closed a deal on a gorgeous 640-acre spread on the Crooked River. And no doubt he thought putting a little money on the home team would help warm up the welcome the newlyweds would get in their new home town.

(Hal, by the way, was himself a pro-level baseball player. He pretty much won Dorothy’s heart on the baseball diamond at Harvard. It was a pretty good bet that he would be trying out for the team himself after they got settled in.)

Certainly Lawson could walk away from the $1,000. It was, after all, less than three hundredths of one percent of his fortune. But he’d be damned if he’d let Dorothy and Hal get off to such a lousy start in their new home town. Not if he could help it.

Could he help it?

As it happened, yes, he could. It was time to go on down to the field and do in the visitors’ bullpen what he’d done so often, in his younger years, on the trading floor.

This jovial and charismatic stock promoter, the chief salesman of the biggest bamboozle of the Gilded Age, knew just how to proceed. Smiling broadly, he made his way down to where the Silver Lake players were resting and catching their breath, waiting for the game to resume.

No doubt he was at his boisterous and hearty best as he stepped up to the members of the visiting ball club, although the records don’t mention that part. What they do mention are his words:

“The drinks are on me!” he roared.

Change in fortune

An hour or two later, at the end of the ninth inning, the final score was 10-9 in favor of Prineville. And Lawson had run up one humdinger of a bar tab. But then, he’d won a $1,000 to pay it off with. And his family’s full and enthusiastic acceptance by the jubilant Prineville community was a done deal.

Which was good — not just for the newlyweds, but for the entire state of Oregon. And that’s because of the other reason I mentioned why the name “Thomas Lawson” might have rung a bell in your memory. It’s because of Lawson’s grandson — Dorothy and Hal’s second child, who was named after his illustrious grandfather.

His name was Tom Lawson McCall, and he grew up to be probably the best and most effective Oregon governor in the state’s history.

Braly, David. “Tales from the Oregon Outback: Prineville:” American Media, 1978

Walth, Brent. “Fire at Eden’s Gate: Tom McCall and the Oregon Story,” OHS Press, 1994

McCall, Dorothy Lawson. “The Copper King’s Daughter,” Binfords, 1972.