Offbeat Oregon: How the Whitman massacre become mythology

Published 4:00 am Thursday, March 28, 2024

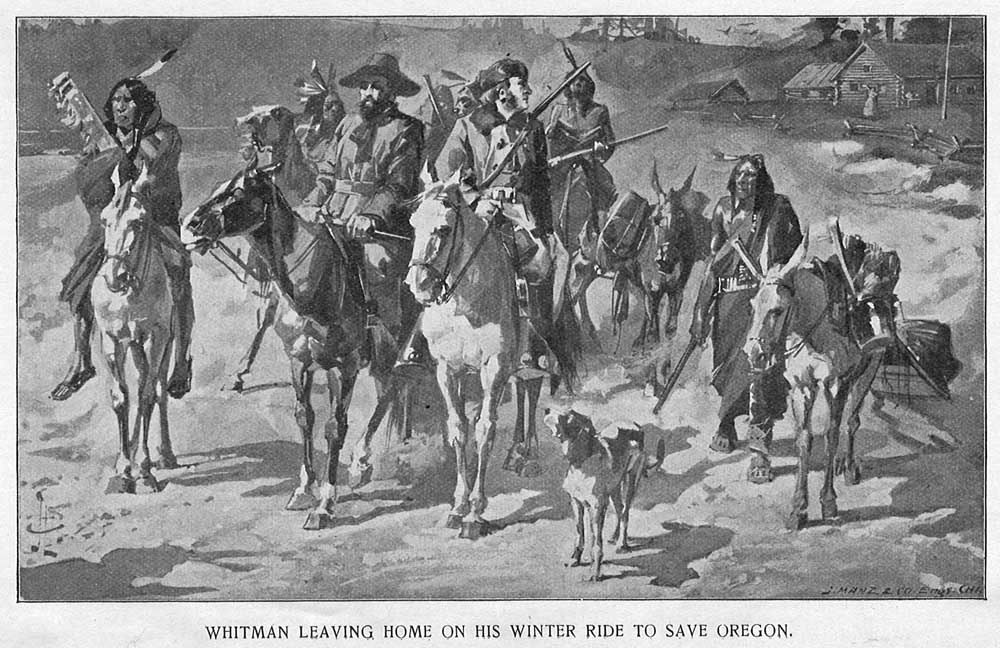

- An artist’s depiction of Marcus Whitman leaving on his wintertime cross-country journey to save his mission from closure, published in Oliver Nixon’s 1894 book. The dog and the mule were eaten along the way to stave off starvation.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series. Visit redmondspokesman.com to read it in its entirety.

Trending

The spark that touched off the powder keg of Indian resentment against Marcus and Narcissa Whitman’s mission station at Waiilatpu came in 1847, in the form of an outbreak of German measles.

This disease most likely was spread by Indian horsemen journeying abroad in other areas, although it’s possible (if unlikely) that it might have arrived the way the Natives suspected it did — from Oregon Trail emigrants staying at the mission. Most Europeans had enough immunity to fight the disease off, although it wasn’t a fun process. Most Indians, though, had no immunity built up. And it killed an enormous percentage of the Indians it touched, especially children.

This was not the Indians’ first experience with a new European disease either. A smallpox outbreak had wrought great slaughter and suffering several years before. So they knew what lay before them. In desperation, they started casting about for a way to prevent it.

Trending

This was all happening in 1847, which was basically the second year after the Oregon Trail really got going. One of the first people to traverse the trail — he probably arrived with the 1846 migration — was a half-Iroquois criminal named Joe Lewis. Lewis stayed at the mission for a few days, then left and found the Cayuse tribe.

Lewis, apparently hoping to cause some trouble that he could exploit to do some looting, told everyone who would listen that the Whitmans were poisoning them. Remembering the tainted meat that the missionaries were leaving around to kill wolves, and the obvious land hunger of the Oregon Trail settlers, the Indians considered it a real possibility. After all, the “Bostons” who were pouring in over the Oregon Trail all seemed to want to take their land, and what better way to facilitate that than by poisoning them off of it as they had the wolves?

To test this theory, the tribe sent three Indians to the mission for measles treatment. Two of them had measles; the third did not.

Of course, measles is one of the most spreadable diseases known to humanity. Whether the third man already had the disease and wasn’t symptomatic yet, or he picked it up from his two sick fellow travelers, he soon had it. There was no medicine in an 1840s physician’s bag of tricks that could even hope to save any of them. All three were soon dead.

After that, the Cayuse chiefs ordered Whitman to leave. He refused. So the chiefs ordered the mission extirpated.

On Nov. 29, 1847, the order was carried out — brutally and thoroughly. Eleven people at the mission were killed, including Marcus Whitman (hacked to death with tomahawks) and Narcissa Whitman (shot to death). A twelfth missionary, none other than Henry Spalding, was on the tribe’s death-warrant list but he was away when the massacre was carried out. When he returned a couple days later, he had his life saved by a priest who warned him to run for his life. With a Cayuse war party in hot pursuit, he just barely made it to safety.

The aftermath

What followed Whitman massacre was, arguably, an absolute smorgasbord for the cynical.

For the settlers who really did want to drive the Cauyuse from their lands and take it over — which was probably most of them — the massacre was convenient. It provided moral cover to spin land theft so that it looked like a quest for justice, at the same time providing “evidence” that the Indians could not be lived with and would have to be culturally incarcerated for the protection of all.

Almost immediately, the provisional government of the Oregon country went to war, forming a militia and marching against the Cayuse tribes, supported eventually by regular U.S. Army troops.

The fighting was very one-sided. The settlers had much better arms, for one thing, and for another, not all the Cayuse tribe members wanted to fight. After just a few years, the resistance fighters had been driven into hiding in the Blue Mountains.

In 1855, the chiefs of the Cayuse sent five tribe members to Oregon City to be tried for the massacre. Most if not all of these five — Tilaukaikt, Tomanhas, Klokamas, Isaiachalkis, and Kimsumpkin were their names — had not been at the mission and had had nothing to do with the massacre. Kimsumpkin testified that everyone who’d been involved in the massacre had been killed in the ensuing fighting. But the five of them knew they were there to pay a blood price for their people so that the war could end.

And, that’s basically what happened. All five were proclaimed guilty following a theatrical performance masquerading as a trial, and promptly hanged in what was almost certainly the Oregon Country’s very first episode of judicial lynching.

But, the war didn’t really end after that. It lingered for another five years with pockets of resistance here and there, and raiding parties making slash-and-run sorties from hideouts in the mountains, until a year or two later, when the tribe gave up its lands and moved to the Umatilla reservation.

In the meantime, among the Protestant missionaries of Whitman’s organization, Henry Spalding — remember him, from Part One of this story, last week? — was piecing together a thunderous whopper using carefully selected bits of the Whitman story, generously leavened with speculation and plenty of straight-up fiction.

It’s not entirely clear what his goal was in doing this. In part, he was settling some personal scores. It was also religious prejudice. A fervid anti-Catholic, he bitterly resented owing his life to that priest who warned him to run for his life after the massacre.

So out of the fairly boring series of events that led to the massacre, Spalding wove a whopper that would literally change the world. Here is the story he had when he finished:

A tall tale is told

Dateline: Fort Vancouver, November 1845: St. Marcus Whitman of Waiilatpu is dining with those treacherous English pig-dogs at Fort Vancouver when word arrives that a small group of Canadian settlers from Manitoba has just arrived. There is much rejoicing, and a young priest forgets himself and crows, “The country will soon be ours!”

Hearing this, Whitman, as soon as he can courteously disengage, runs for his horse, vaults into the saddle and gallops away into the night. Arriving back at his mission house, he hastily puts together his traveling kit. When a weeping Narcissa begs him to wait till spring to travel, he is unmoved by her tears. “I must fare forth unto Washington D.C. and warn our noble President of this perfidious National peril!” he cries as he gallops away in the snow. “There is nary a moment to waste!”

He arrives back east starved and frozen, still clad in ragged buckskins, just in time to stop President Tyler from signing a deal that would have traded away Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and part of Montana to Perfidious Albion in exchange for rights to a cod fishery off the coast of Newfoundland.

St. Marcus paints a glowing picture of the glorious promise of the Oregon Country, convincing the president to scotch the codfish swap. Then he convincingly argues that Oregon will be forever lost to those scheming, crafty Limeys if America does not act fast. Only a great flood of emigrants pouring across the continent and settling in the Oregon Country can stop the British and their “papist” allies from stealing Oregon for themselves.

Despite the well-intentioned obstructionism of Secretary of State Daniel Webster (who really wants that cod fishery), President Tyler leaps to his feet, seizes the presidential bugle and blows a stirring call to arms.

Thus encouraged, St. Marcus sets about in a patriotic frenzy of pamphleteering and public speaking to assemble a mighty armada of prairie schooners crammed with red-blooded American settlers; and next thing you know, St. Marcus is returning in triumph at the head of this massive covered-wagon army, leading thousands of rugged American pioneers to Oregon like a latter-day Moses, foiling the machinations of the British pharaohs and their treacherous Native allies.

And that’s how Marcus Whitman saved Oregon … according to Henry Spalding.

Birth of a national mythology

It’s easy to see how appealing this myth was for the Protestant American settlers of the day. After all, it’s quite true that the British had been hoping to acquire clear title to Oregon. It’s also true that the wagon train Whitman joined for his return trip was the first big wave of covered wagons that poured over the continent on the Oregon Trail. And what had been a trickle became a torrent of American settlers who quickly made any British claim on Oregon impossible to pursue … and brutally pushed aside the Indians everywhere they went.

So for the beleaguered American settlers in the Oregon Country, it must have looked — in retrospect at least — a lot like a case of Whitman bringing the cavalry.

When, shortly after his return, Whitman died in the massacre, it wasn’t hard to interpret that as influenced by British vengefulness. The British, as traders rather than settlers, had much better relations with Indians than Americans did.

The myth got wings and percolated deep into mainstream history in the late 1800s after Whitman College got involved. Whitman College is today one of the best small private liberal-arts colleges west of the Mississippi. But in 1894 it was teetering on the brink of insolvency. A new college president, Stephen Penrose, learned about Henry Spalding’s whopper and bought it hook, line, and sinker. He then spent the next 40 years using it as a fundraising story.

In doing so, he saved the college. But he also injected this phony story into every middle-school American History textbook in the country. And it wasn’t until after the turn of the century that the truth came out. Even then, the myth was so appealing to Golden West boosters that it lingered for decades.

This was especially true in Washington State, where Whitman was revered like a patron saint clear up into the 1960s. In 1953 the state commissioned two identical bronze statues of Whitman, in buckskins with a Bible under his arm. One was placed in the foyer of the state capitol in Olympia and one was sent to Washington D.C.

One place where the myth provided a constant source of frustration was the Indian community, especially the Cayuse tribe. Branded by the myth as a pack of renegade murderers, Cayuse members found themselves shunned even by other tribes, who feared antagonizing the non-Natives and making things even worse for themselves.

And for the better part of two centuries after that, the Cayuse Tribe could not catch a break. In the two world wars the Army came for their horses and pretty much wiped out their population of the legendary ponies that bore their tribal name, requisitioning them for war duty. By the time of the Eisenhower Administration, with its mania for tribal “extinguishment,” the tribe really did look like it was about to become extinct.

But it didn’t.

In recent years, the collapse of the Golden West triumphalist mythology in general and of the Whitman martyrdom myth in particular has come as a welcome relief to them. And the success of the Wildhorse Resort and Casino in Pendleton has finally given them a taste of the life most of us nontribal members take for granted. It’s a welcome change, but it was a long time coming. Now if only we could find a breeding pair of their famous horses, and bring Cayuse ponies back.

Revisiting the narrative

In recent years there has been a decided movement away from the Marcus Whitman myth. The statue in D.C. was pulled in 2021 and given to the city of Walla Walla. A copy of the statue given to Whitman College in 1991 was tucked away in a seldom-visited corner of campus, close to the railroad tracks. Faculty members joked that maybe someone was hoping it would get run over in a derailment. And despite their newfound reclamation of some status and relative prosperity, the surviving members of the Cayuse tribe still feel the sting of having been branded as a pack of lawless murderers, the “bloodthirsty savages who martyred an innocent holy man.”

Even today, nearly 200 years later, it’s not a topic they much care to make chit-chat about.

But stories, legends and myths are their own kind of history. This myth, we can now clearly see, was a tissue of lies and half-truths crafted for propaganda purposes, but it profoundly shaped Oregon and the West. The damage it did can’t be undone now … the best we can do is, having set the record straight, use it as a lens to better understand the swindlers who crafted it, and the people who over the years got swindled into using it to make sense of their world.

“Murder at the Mission,” a book by Blaine Harden published in 2021 by Viking

“Whitman ‘Massacre’: Are We Past the Whitewashing of History?” an article by Cassandra Tate published Nov. 28, 2017, in Crosscut by Cascade Public Media

“Whitman Murders,” an article by Cameron Addis published in 2023 by Oregon Encyclopedia

“How Marcus Whitman Saved Oregon,” an entirely unreliable book by Oliver Nixon published in 1894 by Star Publishing

“The Far Corner,” a book by Stewart Holbrook published in 1973 by Comstock.