Part 2: Bloody 1925 prison break ended badly for everyone involved

Published 2:00 am Tuesday, May 23, 2023

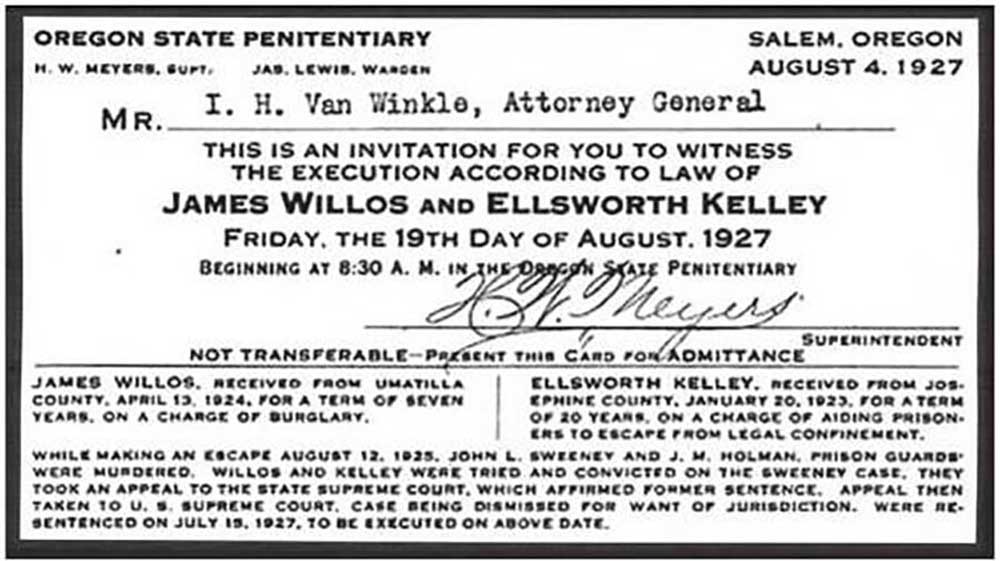

- A ticket to the execution of convicts Ellsworth Kelley and James Willos after their recapture. This execution date was canceled, but the two were hanged the following year.

Editors note: This is the second in a series titled “Bloody 1925 prison break ended badly for everyone involved. In Part 1, the prisoner’s made their escape. Read the piece in its entirety at redmondspokesman.com

The three survivors of an already bloody prison break made their way to a farm just outside of New Era, where they threw themselves on the mercy of the farmer there, C.L. Newman. It’s not clear whether Newman was part of the New Era Spiritual Society commune, but he probably was, because he took a very Mount of Olives Discourse-inspired approach with the convicts, taking them in and feeding them and letting them rest peacefully. He didn’t report the convicts’ visit until well after they were on their way, which let him in for some bitter words from local officials. Newman, though, bluntly replied that he was not going to put his family’s safety at risk by taking sides in a quarrel that he saw himself as having no part in.

Eventually, though, the convicts did have to move on. After writing an account of the breakout in which they claimed “Oregon” Jones had done all the killing and pledged never to be taken alive, they left Newman’s farmstead and aimed to get far enough away to make a clean break.

Near the town of Bingen in southern Washington, Murray, the leader of the crew, wanted to go east. But Kelley and Willos thought north was a better option. So the gang split up.

Murray drifted into a trainyard in Centralia, where he started looking for a morally flexible drifter who might help him pull a holdup to get some traveling money.

He found one in Phillip Carson, a 26-year-old hobo from Portland … or so he thought. Carson paid to rent a cheap hotel room in which they could plan the job, and told him he knew an experienced stick-up man who would help for a cut of the take. Then, out Carson went to get his friend … from the local police station. One of the cops on duty, C.D. Pilling, quickly changed into civilian clothes and came back with him.

Soon, Carson was introducing Murray to Pilling, and a few minutes later Pilling and Murray had hatched a full plan to knock over a nearby roadhouse.

Then Carson and Pilling went out to hire a car and returned with George Barner, the mayor of Centralia, behind the wheel of his own car.

Needless to say, Murray never made it to the roadhouse for the stick-up. Back he went to Salem in careful custody to face his reckoning.

But he never received it. On May 10, 1926, as it became increasingly clear that he was headed straight to the gallows, Murray hanged himself in his holding cell.

By that time, the other two were back in custody as well. Ellsworth Kelly and James Willos got off to a bad start on their own when, sticking around Bingen to try to raise traveling money, they burgled E.G. Lewis’s general store. The haul was pitiful — about $18 — but they helped themselves to some of the merchandise as well. This, though, turned out to be a huge mistake, because they stole new shoes for themselves, and left the packaging behind, which is how police learned that whoever robbed the store wore the same size shoes as two of the escaped prisoners from Oregon.

They then broke into the town marshal’s house, not realizing that he was still inside and asleep. Luckily for everyone involved he did not wake up. They stole some money, tried and failed to steal the marshal’s car, and continued on their way. Farther down the road they found an Overland sedan, which they managed to start, and in which they fled.

But they wouldn’t get far in it. The next day, a posse of Multnomah County cops driving to Bingen saw a track of freshly smashed-down foliage leading off the highway through brush into a deep canyon. Leaving their car at the road, the four of them stealthily followed the trail on foot to where the car was parked out of sight of the road, and both convicts were sitting on the ground in front of it with sandwiches in their hands. Their surprise was complete and they were back in Salem almost before Murray was.

In his suicide note, Murray tried to save the other two from the noose by claiming he had shot one guard, “Oregon” Jones had shot the other, and Kelley and Willos hadn’t even fired a gun. He needn’t have bothered. Under the law, when an illegal operation ends with innocent blood spilled, every member of the criminal conspiracy is considered just as responsible as every other member.

It took some time. Convictions were appealed, and the Supreme Court even had to weigh in. But in the end, it was all for nothing, and finally, on April 20, 1928, both Ellsworth Kelley and James Willos were hanged.

Changes at the prison

The 1925 prison break had a big effect on the state prison. Warden Dalrymple, as mentioned before, had been given the job for political reasons, and he was paired up with J.V. Starrett as the state parole officer. Starrett was on the Ku Klux Klan’s payroll (he was a Kleagle or something like that) and had done a yeoman’s job getting out the “Klown vote” to elect Pierce as governor. The position of parole officer had been his reward.

But like a lot of people to whom membership in a gang of secret vigilante terrorists was appealing, Starrett was always hungry for more power and contemptuous of rules. By 1925 Starrett and Dalrymple were openly feuding and everyone at the prison, guards and prisoners alike, had learned how to play them off against each other.

That, of course, all came to a screeching halt after this bloody fiasco.

Both Dalrymple and Starrett were given their walking papers, along with five guards who “retired early,” and the prison was taken over by Warden J.W. Lillie, former sheriff of Gilliam County. Order was restored, and the next time a disturbance broke out — a food-fight in the dining hall that escalated into a 200-man riot — Warden Lillie himself ran to the scene with a gun and fired over a dozen shots into the crowd, critically wounding at least one man.

The Oregon State Peniteniary was always a pretty awful place. But under Lillie, it became, at least, a little more predictable and less dangerous to its neighbors.

A Cycle of Crisis and Violence: The Oregon State Penitentiary, 1866-1968, a master’s thesis by Joseph Willard Laythe published in 1992 by Portland State University; archives of Roseburg News-Review and Oregon Statesman: March 1924, August 1925, May 1926, April 1927, April 1928; correspondence with Peter Bellant of Portland