Man gets community service for arson fire that destroyed Redmond meatpacking plant

Published 2:30 pm Tuesday, November 1, 2022

- Joseph Dibee in an FBI photo taken in the early 1990s.

A federal judge Tuesday sentenced eco-saboteur Joseph M. Dibee to community service, rejecting the government’s call for a seven-year-plus prison term for the Seattle man who was a fugitive for more than a decade before he pleaded guilty to committing two arsons in Oregon and California including a Redmond meatpacking plant.

“I’m truly sorry for all the events that have happened. I haven’t been involved in this type of activity for many years,” Dibee, 54, told U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken, appearing by video for his sentencing in federal court in Eugene. “I’ve moved on with my life. It was a mistake many years ago — many, many years ago — and I paid a really heavy price for it.”

Assistant U.S. Attorney Quinn Harrington urged a prison term of seven years and three months, arguing Dibee shouldn’t be “rewarded with a lower sentence after fleeing accountability.”

At the time of his arsons, Dibee was highly educated with a supportive family, yet he took more of a leadership role in igniting fires when some of his co-defendants served more as lookouts, Harrington said.

Defense lawyer Matthew Schindler argued for a sentence of time-served — the two years and five months Dibee was in jail before his pretrial release. During his time in custody, Dibee suffered a broken jaw from an assault by a white supremacist that has left him permanently disfigured and was the first to contract COVID-19 in Multnomah County’s Inverness Jail, his lawyer said.

“He served an entire 29 months that were just incredibly harsh and difficult,” Schindler said.

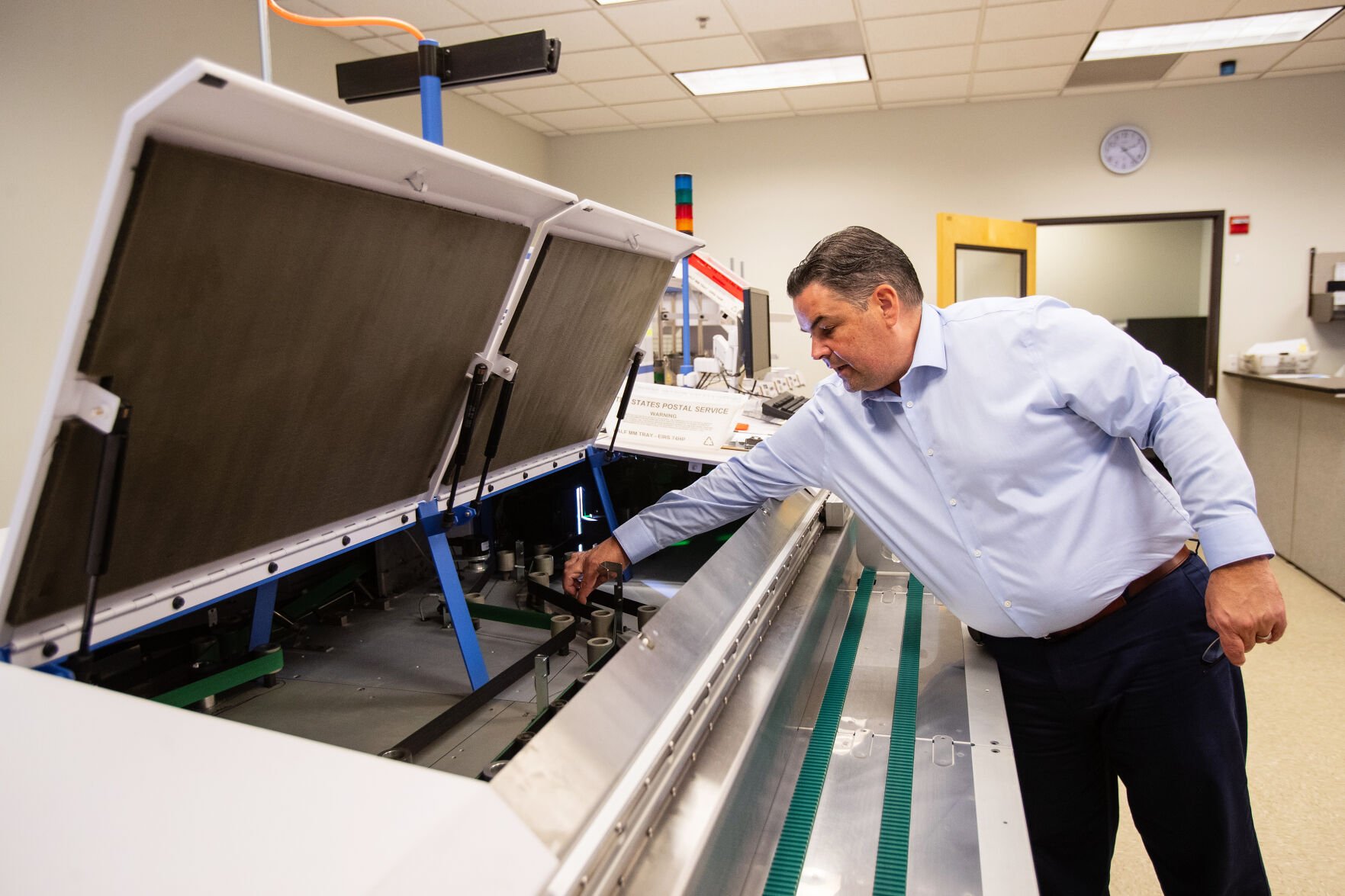

Aiken, who has been with the case since the beginning about three decades ago, said she believed Dibee has recognized his wrongs. She remains impressed with how he’s working now to use his “incredible engineering skills” to help Indigenous tribes in Alaska, she said.

Dibee has been working with The Native Conservancy Project, a community nonprofit, to help track kelp production yields in Indigenous ocean communities. The kelp farming is intended to provide the communities with a stable protein source and added income as salmon runs have dramatically fallen from overfishing and climate change, according to Dibee and his lawyer.

The judge said she hopes Dibee uses this time as an opportunity to “be a contributor to the greater good” and show younger people “how to make change through the rule of law.”

“You have demonstrated you have learned lessons, although belatedly,” Aiken said.

She ordered that he complete 1,000 hours of community service in the next three years and pay about $1.3 million in restitution, an amount shared by his co-defendants.

Dibee, a fugitive for 12 years who was finally tracked down in Cuba in August 2018, pleaded guilty in April to two counts of conspiracy to commit arson and one count of arson in a string of attacks that destroyed or damaged environmental targets in Oregon and California more than two decades ago. He was held in Cuba based on an Interpol notice reporting U.S. arrest warrants and turned over to FBI agents.

Federal investigators said Dibee was part of the largest group of eco-saboteurs ever taken down by the FBI. They called themselves “The Family” — more than a dozen people who committed crimes in the name of the Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front — and caused an estimated $40 million in damage from 1996 to 2005.

He’s the 12th person to be sentenced in the case. One remains a fugitive, Josephine Sunshine Overaker, who is still listed on a FBI terrorism most wanted list. The sentences of his co-defendants have ranged from just over three years to 13 years in prison.

Dibee pleaded guilty to engaging in a conspiracy to set fire to government buildings and destroy other property, driven by “ideology, and as part of ‘direct actions,’” from October 1996 through December 2005, according to Harrington.

Dibee also pleaded guilty to arson tied to a fire he helped set at the Cavel West Inc. meatpacking plant in Redmond in July 1997 and to conspiracy to commit arson in a fire at the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s wild horse corrals near Litchfield, California, in October 2001.

The judge said she weighed Dibee’s decision to flee the country to escape his indictment. She also considered that Dibee suffered “extraordinary collateral consequences” from what his lawyer called Dibee’s torture in Cuba, his attack in jail followed by “inappropriate negligent medical care” that resulted in untreated facial fractures as well as his contracting of COVID-19.

Aiken said she believed Dibee was a changed man. Schindler and Dibee’s prior defense lawyer have said Dibee is now seeking to effect change through the research and development of better environmental practices that would financially benefit companies.

The prosecution of the case, Aiken said, was pivotal in impressing upon environmental activists the importance of “not using anger and violence as a weapon for change.”

She also acknowledged that in society to this day, “people are taking decisions into their own hands and acting out in ways that are both criminal and inappropriate and dangerous.”

Before issuing her sentence, she quoted South African anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela: “Great anger and violence can never build a nation.”

The buildings at Cavel West were destroyed, with the loss estimated to exceed the insured value of $1.2 million, according to court records. The fire was designed to end the processing of meat from wild horses slaughtered by the plant.

A co-conspirator recruited Dibee to help plan and burn down Cavel West after meeting him at a protest. Dibee scouted out the location and then reported back that they’d need more people. On July 20, 1997, Dibee and a crew returned to Cavel West, wearing dark clothing, masks and gloves.

Dibee brought timers he created and a fuel mixture. He drilled holes into the building to pour flammable gel into, stuffed rags into the holes and placed buckets under the rags. One of three explosive devices ignited prematurely, the building caught fire and he and others fled.

They all ran back to a van, drove to the staging area, took off their clothes, shoes, masks and gloves and put them in a previously dug hole, poured muriatic acid on them and covered the hole with dirt, according to prosecutors.

Four years later in California, Dibee helped destroy the Bureau of Land Management’s wild horse corrals. Prosecutors said he played a significant role in drawing accomplices from Canada and hosting them at his house in Seattle, where they built explosives. One co-defendant said Dibee suggested Litchfield as a target.

On the ride from Seattle to California, an accomplice described Dibee as acting “very cocky” bragging about all the property damage he had done, according to prosecutors. On Oct. 15, 2001, Dibee and accomplices arrived in Litchfield to release the horses and burn down the corrals.

They placed four explosives around the corrals, including one in the hay storage pole barn that ignited and cut fences to release horses. The release so close to a highway caused safety hazards. The barn ignited and was destroyed, causing about $207,500 in damage.

“Setting fires to help the environment is inherently an absurd concept,” Harrington wrote in his memo.

They also posed significant dangers. “Dibee’s actions were also foolish and futile. Setting fires, damaging property, and intimidating people is not a legitimate form of political activism,” the prosecutor argued.

After learning of potential charges in 2005, Dibee fled. He moved to Syria before fleeing to Russia around fall 2010. He was stopped in Cuba in August 2018, traveling with a Syrian passport. Dibee has said in court previously that he was flying from El Salvador back to Russia through Havana using a Syrian passport when he was detained and turned over to the FBI.

The judge said she had no doubt that Dibee was mistreated while held in Cuba. His lawyer said he was subjected to “torture,” by Cuban military intelligence officers. In one incident recounted by Aiken at sentencing, Dibee apparently was told if he didn’t own up to what he had done, they’d take him in an airplane and drop him in the ocean and no one would ever know where he was.

Aiken also noted that Dibee was “brutally attacked and injured” in jail before he was released on Jan. 12, 2021.

Since his release from jail to care for his father, who is terminally ill, Dibee has not violated any of his supervision conditions, the judge said.

At the time of the Cavel West arson, Dibee was 29. With a bachelor of science degree from Seattle University and an engineering license, he was employed by a consulting company that did work with Apple. When he committed the Litchfield arson, he was 33, worked for Microsoft, earning a $150,000 annual salary, according to prosecutors.

While Dibee may not have participated in as many arsons as his co-defendants, he was older, more educated than some and “knew better,” and then went on the run while his accomplices faced their days in court and served lengthy prison terms, Harrington argued.

“Mr. Dibee was one of the only adults in the room and had a college education, respected career, and six-figure salary at a major tech company,” Harrington wrote to the court. “A sentence below that of his co-conspirators would be an unwarranted disparity.”

Aiken and Schindler credited retired U.S. Magistrate Judge Thomas M. Coffin, who served as a mediation judge in the case, for helping each side reach a “fair and reasonable settlement” and resolution to the case that could have ended up being prosecuted in three federal courts in three different states.

Arson charges against Dibee stemming from a 1998 fire at a U.S. Department of Agriculture building in Olympia, Washington, were dropped as part of the plea deal.