Offbeat Oregon: Little-known activist stopped state plan for forced sterilizations

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, November 21, 2018

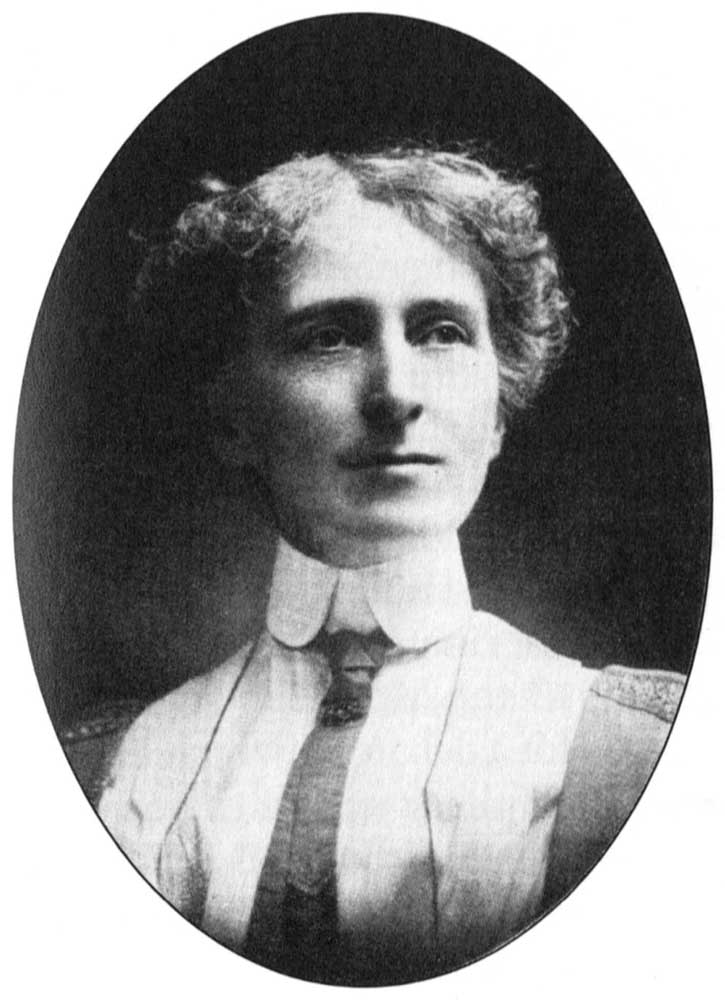

- Lora Little as she appeared in her 40s.(Image: Oregon Historical Society)

In 1913, the Oregon state legislature passed a eugenic-sterilization law that had been written for it by one of the state’s most prominent citizens.

The law’s author was Bethenia Owens-Adair, the first female medical doctor in Oregon history. She had retired from practice eight years earlier and devoted herself to three big social-activism projects: women’s suffrage, the temperance movement — and eugenics.

She was winning all three of these battles. The previous November, Oregon voters had enacted full voting rights for women in state and local elections. Prohibition, she knew (or at least strongly suspected), would follow just as soon as all the newly enfranchised women could get to the polls for the 1914 election.

And the sterilization law’s passage that year represented victory on the third front: eugenics.

Essentially, eugenics is an attempt to apply the techniques of dog breeding to the enhancement of the human gene pool. One could not, of course, simply kill the less desirable specimens, the way dog breeders once did. But one could, with the right kind of legislation, spay or neuter them. And that, essentially, was the solution Dr. Owens-Adair recommended.

Her victory had been a long time coming. She’d first introduced a eugenics bill in the legislature, with the help of her state rep, in 1907. It would have required that “habitual criminals, moral degenerates and sexual perverts” — including people caught engaging in “the crime against nature” — a euphemism for homosexual activity — “or other gross, bestial and perverted sexual habits” — should, before being released from state institutions (prison, insane asylum, juvenile detention, etc.) be sterilized.

The bill didn’t pass in 1907. Eugenics hadn’t quite come into its own as a topic of popular interest yet.

Time was on its side, though. In scientific circles, the theory of hard Darwinian gene-driven evolution was becoming dominant.

And it wasn’t much of a leap from “our genes control our lives” to “hey, that drunk guy in the corner of the bar must have really lousy genes, let’s do something to keep him from passing them on.”

That sentiment didn’t have enough support in 1907. Or in 1909, when Dr. Owens-Adair reintroduced it. But in 1913, it did — enough support to override the governor’s veto. (Gov. West took care to explain, though, that while he agreed with the bill’s sentiment, he didn’t think it provided enough protection against possible abuse.)

But that’s when the irresistible force that was Bethenia Owens-Adair encountered the immovable object that was Lara Little.

Lora Cornelia Little was born in 1856 in Minnesota. She married an engineer in the late 1880s, and settled into the life of a rural housewife. Soon the couple had a son, Kenneth.

The turning point in her life came in 1896 when her son was vaccinated for smallpox. Over the subsequent year or so, the little tyke started getting ear infections, and finally he caught diphtheria and died.

Lora Little was crushed. And angry. Very, very angry — especially as well-meaning social-hygienists, many of them physicians, started pushing for the vaccination that had, she thought, killed her son to be made mandatory for all Minneapolis schoolchildren.

Little developed a cordial and enduring hatred of the mainstream medical profession, and over the subsequent decade she developed a medical philosophy of her own — one somewhat similar to that of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, or of Sylvester Graham (the inventor of the Graham Cracker). Diseases of all types, she posited, were symptoms of an unbalanced life, and eating right (whole grains, lots of vegetables, very little meat) and living right (no booze or unnecessary sex, getting proper sleep, etc.) was the key to staying healthy and never getting sick.

In 1898 Little started publishing a magazine called “Liberator.” The magazine was a big success, although it appears to have wrecked her marriage. In 1911, she moved to Portland and settled in the Mount Scott neighborhood. She immediately opened a health institute, the Little School of Health, and began seeing patients and teaching classes. She also began writing letters to the editor of the Portland Morning Oregonian — lots of letters. She started a column in the neighborhood weekly, the Mount Scott Herald, titled “Health in the Suburbs.”

She was a force to be reckoned with in her new home. Portraits of her show a poised, confident woman in the high celluloid collar and necktie commonly worn by businessmen of the day, with steady, fearless eyes.

And it was a year or two after Little established herself in Portland that Bethenia Owens-Adair launched her successful bid to get mandatory sterilization of “undesirables” legalized.

Now, of course, eugenic sterilization was not Little’s primary target. That, in memory of little Kenneth, would always be vaccination. But she saw the two issues as closely related. In both cases, mainstream physicians were asserting control over other people’s bodies. And she also saw that the same spirit animated both acts — the technocratic spirit of the Progressive movement, the spirit that looked to mold and guide society in more virtuous ways by whatever means the relevant experts thought best, with scant regard for individual rights.

“A bull in a china shop is a gentle, constructive creature compared with a lot of prim and more or less pious folks when they want to clean up society and the world,” she wrote in her column in the Mount Scott Herald. “Mr. Sudden Reformer sees something he does not like in one of his fellow citizens. Very likely it is a reprehensible thing. Plenty of evils exist in the lives and habits of all classes. This would be a thing of which Mr. Sudden Reformer is not himself guilty. Therefore he hates it with a mighty loathing.”

To Dr. Owens-Adair’s dismay, voters quashed the law by a substantial majority — 56 percent of them voted to throw it out. Dr. Owens-Adair had lost the battle, but not the war. Her next eugenic-sterilization bill contained more checks and balances, more processes of notification and appeal, and called for an actual state eugenics commission to provide oversight. And in 1917, it passed.

But by that time Lora Little was out of the picture, having left town to join the national American Medical Liberty League.

As for Owens-Adair’s sterilization act, it went into effect and over the subsequent 75 years the state quietly sterilized more than 2,600 people — troubled youths in juvenile detention facilities, insane-asylum inmates, members of poor families selected by social workers, and penitentiary prisoners. Finally, in 1983, the state eugenics board — renamed, for public-relations reasons, the Board of Social Protection — was quietly dissolved, bringing the whole ignoble experiment to an end.

It was bad. But had it not been for Lora Little, it likely would have been a good deal worse.

(Sources: Johnson, Robert D. “The Myth of the Harmonious City: Will Daly, Lora Little, and the Hidden Face of Progressive-Era Portland,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Sep 1998; Largent, Mark A. “’The Greatest Curse of the Race’: Eugenic Sterilization in Oregon, 1909-1983,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Jun 2002; Currey, Linda L. The Oregon eugenic movement : Bethenia Angelina Owens-Adair (master’s dissertation). Corvallis: OSU Scholars’ Bank, 1977)

— Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. Contact: finn2@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.