Maragas Winery making name north of Redmond

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, January 3, 2018

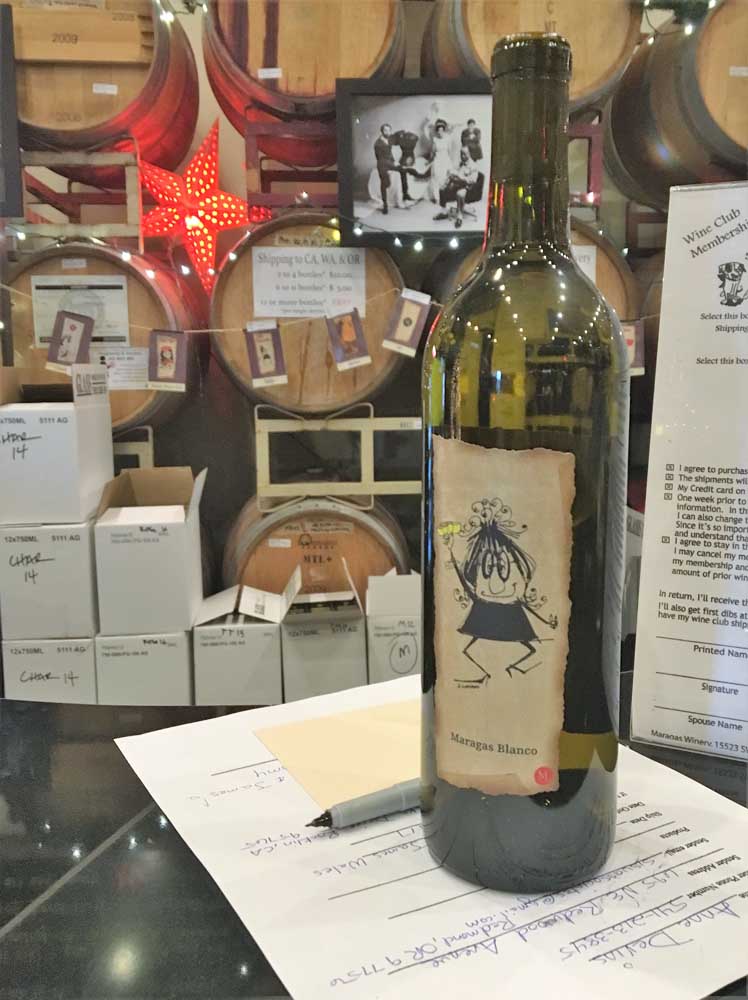

- A bottle of wine from Maragas Winery. (Joseph Jordan/Photo for the Spokesman)

An icy fog curls around the low trees that line the driveway that leads off the highway north of Redmond.

Trending

Frost clings to the rooftop of the big barn, and smears the windshield of pickup truck parked in the lot next to it. The feeling is wintry, almost spooky, with the Cascades to the west and Smith Rock to the southeast both obscured on the horizon. But follow the signs that line the gravel, around the corner of a big white tent and to a door on the far side of the barn. Open that door. Inside it is warm and light.

This is the headquarters of the Maragas Winery, and inside the barn smells richly of wood.

Two hundred and sixty-eight wooden barrels, to be precise, each full of wine made in a style that dates back generations, to the Greek island of Crete, where Doug Maragas’ ancestors still have a vineyard. Maragas, 53, has decorated this cavernous room with photographs of that vineyard, along with artwork by his mother, Joanne Lattavo.

Trending

Lattavo’s comic drawings also decorate the labels Maragas puts on his bottles.

“She was the epitome of a beatnik,” says Maragas. “Wore all black, artist, was into poetry, the whole thing.”

The art and photographs help give the room an elegant, welcoming feel, which is part of Maragas’ goal. Though his wines are sold in stores and win awards in California, he likes the idea that people can come out and see the process for themselves.

“People are always curious,” he says, surveying the rows of barrels from a bench next to a fireplace. These barrels are stacked three and four high, on massive metal racks that tower over the people who are working even as Maragas speaks, moving down the rows with a ladder to examine the quality of the still-fermenting spirits.

Oenology — the science wine and winemaking — is a deep field, awash both in ancient knowledge and constant experimentation. Maragas, who left a career in the law to take up winemaking, is passionate about both. He describes his process as “old world.”. But he has also had to adapt to Central Oregon’s distinct climate, with its short growing season, long summer days, chilly nights, and scant rainfall.

Most people, when picturing a vineyard, will probably imagine the long rows of grapevines, strung as high as a man’s head, that can be found in California or Italy. If Maragas tried to grow grapes that way, they’d die in short order. Instead, he keeps his vines close to the ground, where the radiant heat from the daytime sun keeps them warm through the cold high desert nights. This is just one of the techniques Maragas employs.

“There are great wines being made all over the place,” he says, his slender and handsome face thoughtful. “It’s not how you trellis or how they look isn’t really indicative of a great wine-growing region. It’s indicative of how you grow grapes in that region to be great wines.”

It’s time-consuming. Maragas is not just a vintner, he’s a farmer, a marketer, a salesman. Many days are spent in backbreaking physical labor, digging holes for trellises. (Maragas estimates he’s dug twenty thousand holes since starting the winery 19 years ago.)

He works at least 75 hours a week from February through December to make it come together. The only month off is January, when the wine is all aging in barrels and it’s too cold to grow anything. Maragas says he hopes to get some down time next year, though he doesn’t seem sure.

“It’s OK, because I like what I do. If it was something that I didn’t like, it would be a living hell,” he says, laughing at the prospect that he wouldn’t love his work.