How Marie Dorion earned her story as ‘Oregon’s Revenant’

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, August 9, 2017

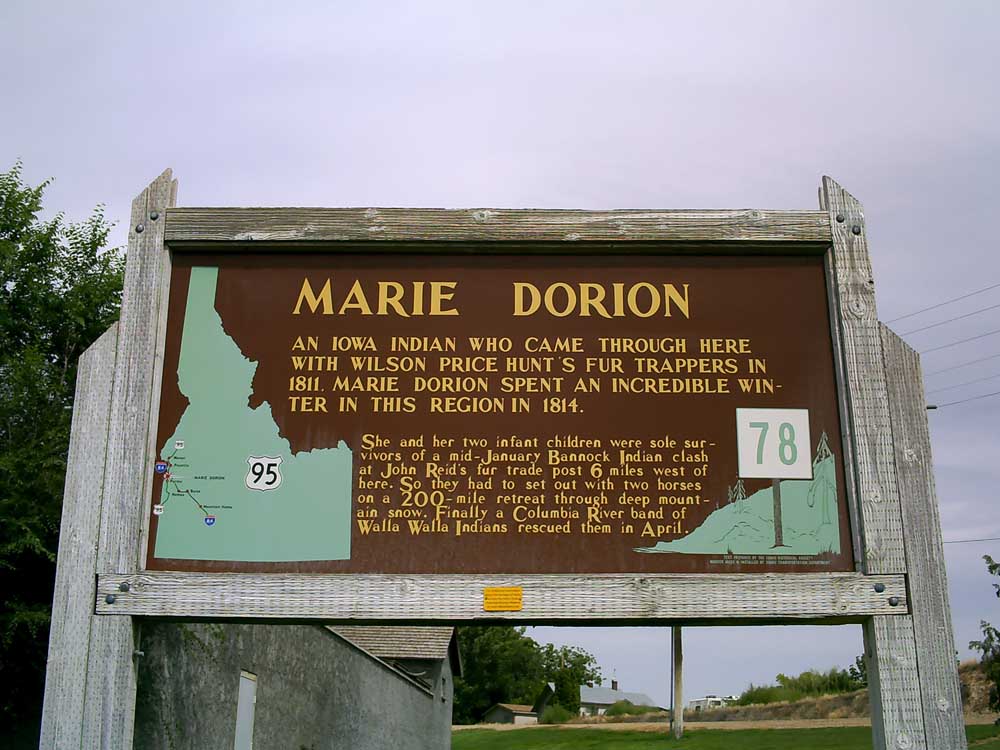

- This historical marker near Fort Boise commemorates the winter Marie Dorion spent in the Idaho wilderness en route back to Astoria in the winter of early 1814. (Rebecca Maxwell/HMDb.org/Submitted photo)

Marie Dorion’s contribution to whatever success the Astorian party enjoyed on its disastrous trip to Oregon was considerable, most likely greater than past historians have conceded. By her presence with her two small boys, she telegraphed the peaceful intentions of the party to any nervous Native Americans they might meet along the way — who might, understandably, interpret a band of 60 heavily armed, fiercely bearded mountain-man types as a war party and react accordingly.

But on that expedition, most of what she did was amaze everyone with her stoicism and quiet competence as she took care of the children, foraged for food, and even gave birth to a third child en route.

This third child died eight days after he was born; it is very difficult to keep a newborn baby alive under conditions of ongoing starvation. But Marie and her entire family made it alive to Fort Astoria, which is more than can be said for 25 percent of the men in the party.

Still, stoic competence and surprising survival are not the sort of feats that inspired historian Greg Shine and Oregonian writer Joseph Rose to call Marie “the Revenant of Oregon,” in a nod to the highly acclaimed 2015 movie about a grizzly-mauled mountain man’s 200-mile journey to get revenge on the men who left him for dead.

It was Marie’s second journey into the Idaho wilderness that clinched that “Revenant” title for her.

In July of 1813 — literally the very next year after she and the 44 other surviving members of the Astorian overland party straggled, starving and exhausted, into Fort Astoria at the end of their epic journey — Marie and her husband, Pierre, were packing their two children up for another journey into the wilderness that had nearly killed them.

This time, the plan was to set up a string of trading posts and start collecting beaver pelts to be turned into fetching headgear for well-dressed European gentlemen.

Under the direction of John Reed, the beaver trappers and traders spent the summer and early fall getting trading posts built and establishing relationships with Shoshone tribe members in the Snake River area. Then winter came along. This time, though, Marie and her kids were ready for it. With Reed and several other members of the party, they were holed up in the expedition’s main trading post, well supplied with everything they’d need to get through a Blue Mountain winter.

But then came the evening of Jan. 10, when a friendly Shoshone tribe member came to warn her that the neighboring Bannock tribe was making trouble. These “bad Snakes,” as some sources call them, had started burning the Pacific Fur Company’s outposts and killing the traders and trappers. The Bannock war party had just laid waste one of the camps, and was on its way to another … the one at which Pierre Dorion was stationed.

Marie, very alarmed, thanked and fed the visitor, sent him on his way home, and packed her stuff. She and the two boys were going to go out into the snow, racing with the marauding Bannocks to get to Pierre in time to warn him.

She was three days getting there, trudging through knee-deep snow and leading her horse with the two boys sitting on it. And she got there just a few hours too late.

Trapper Gilles LeClerc met her as she approached the outpost, staggering in the snow, weak from loss of blood. He was the only survivor. Everyone else had been robbed and murdered. Marie was now a widow.

There was nothing to do now but turn around and follow the trail Marie had broken through the snow, back to the main outpost. Luckily, the marauders hadn’t quite managed to catch all the horses, and Marie was able to capture two of them; so all four of them were able to ride on the journey back.

Two days later, LeClerc succumbed to his injuries. Marie and the boys pressed on. But at the post, they found not the welcoming fires and nourishing food they’d expected, but charred and blackened walls with a few bones in them. The main trading post had been wiped out and burned down. Marie and the boys were on their own, a good 200 miles away from the nearest source of help.

Marie set out immediately, going northwest, making for the Columbia River area where she knew the Native Americans to be friendly.

They struggled through the snowdrifts to the Snake River, swam it (presumably 3-year-old Paul and 6-year-old Baptiste rode across the river on the horses, but Marie probably had to swim). They forged on through what’s now eastern Oregon. But then, as they reached the Blue Mountains, one of the horses collapsed, unable to continue.

Marie decided it was time to stop. She built a rude but cozy shelter and installed her family in it. She built a fire to warm the boys, then slaughtered the horses and started smoking the meat.

The three of them lived in that tight shelter in the snowy mountains, surrounded by drifts and battered by blizzards, for 53 days. They lived primarily on smoked horsemeat, of course, augmented by a few frozen berries, the inner bark of trees, and small rodents that Marie caught in snares made from horsehair.

An early Spring thaw hit their camp in March, just as their horsemeat supply was almost exhausted. Marie packed up the children and the remaining horse meat and the three of them left their little shelter.

But two days later a blizzard struck. Trying to forge on, Marie became snow-blind, and was forced to stop, rig up another shelter (even cruder this time) and convalesce for three days.

Finally, the food exhausted, she ventured out with the boys for a final desperate push. And, fifteen days after they left their little shelter, they reached the plains — and Marie saw campfire smoke.

Unsure if it was friend or foe, she cached the boys behind a rock and approached the village. By the time she reached it, her strength was gone and she was literally on her hands and knees.

Luck was with her. It was a friendly tribe of Walla Wallas.

Perhaps because she lacks a charismatic name like “Sacagawea,” Marie Dorion is not much talked about today, and has never appeared on U.S. currency or anything like that. But her feat of surviving over the winter in some of the most hostile wilderness in the continent with two small boys in tow made her famous in her day.

The Astorian project ended the following year as a casualty of the War of 1812. Out on the edge of the known world, with British rivals just across the river from them, John Jacob Astor’s traders knew their best bet was to sell Fort Astoria to the British and call it quits. The fort was promptly renamed Fort George.

(Sources: Rarihokwats of Ontario, Canada. “Four Arrows Draft Historical-Genealogical Report on Pierre Dorion,” Historical Marker Database, hmdb.org, 02 Oct. 2002; Gulick, Bill. Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 1991; Jewett, Wayne. “Marie Dorion and the Astoria Expedition”, Wild West magazine, October 2000)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn2@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.