Cold snaps cause unintended consequences

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, June 14, 2017

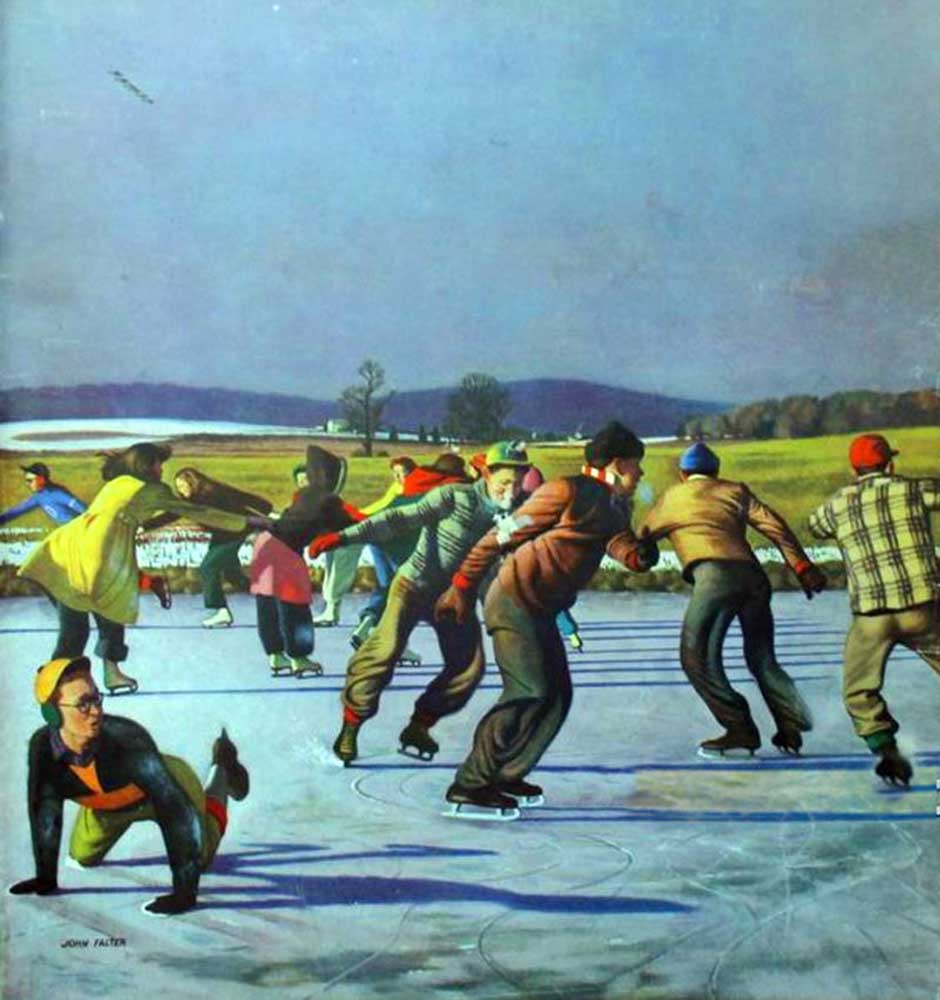

- This painting of skaters sporting about on a frozen lake is from the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, Jan. 26, 1952. This is a scene that, while common enough in the Midwest, has only been staged on the lakes of the Willamette Valley once, in 1949.(Saturday Evening Post/Submitted photo)

As late spring warms up an exhausted and weatherbeaten Willamette Valley, Oregonians are looking back on one of the grimmest winters they can remember.

But memorable though it was, the winter of 2016-17 — with its month-long cold snap and torrential rains — wasn’t that much of an outlier.

The worst cold snap in living memory is probably the winter of 1948-49. That’s the winter thousands of Oregonians learned to ice skate … on Cottage Grove Reservoir.

The ugly weather started on Dec. 12 in 1948, according to back issues of the Cottage Grove Sentinel. For more than a month and a half, the temperature never got out of the teens, and stayed in single digits much of the time. By the last day of January, the cold snap had broken records for both length and depth; the mercury bottomed out at one degree below zero on Jan. 24.

By that time, someone had discovered that the 6- to 10-inch sheet of ice covering Cottage Grove Reservoir from shore to shore was thick enough to support foot traffic. On Jan. 10, the day the mercury plunged to 7 degrees, and someone went down to the lake with a pair of ice skates.

Soon skaters of all ages had hit the lake. On one day, the Sentinel reports, a crowd of 1,500 was down there, ranging in age from toddlers to 91-year-old lumber patriarch A.L. Woodard — who, according to the newspaper, “took off across the lake where it was a mile from shore to shore and returned as though it were a daily habit.”

It wasn’t as if there was anything else to do. Cottage Grove’s timber-based economy had skidded to a halt when the temperatures dropped below 10 degrees. Mills in Western Oregon just weren’t built to work in such conditions; and log trucks and skid loaders struggled to stay on the icy, snowy logging roads and landings.

Of course, ice skates were not a regularly stocked item in Cottage Grove’s sporting-goods establishments. No problem; roller skates were, and most Cottage Grove youths had a pair that were used in warmer weather. It wasn’t much trouble for the local millwrights and fabricators to remove the wheels, sand a couple of old files smooth, and weld them to the skates’ trucks.

The Sentinel reports that the cold snap wasn’t the coldest — Christmas Eve on 1924 had seen 7 degrees below zero; and it wasn’t the most snow: that honor went to the 15 inches that fell on Feb. 24, 1917. But no cold snap, before or since, has approached this one’s depth and duration.

There have been some bad ones since then, of course. The cold snap of 1972 saw temperatures at 12 degrees below zero on Dec. 8, 1972, at the Eugene Airport — which is the coldest weather ever recorded there. And more recently, the cold snap of December 2013 got well down into the single digits.

Of course, when temperatures in the valley get down that low, pipes burst and engine blocks freeze; but there was one cold snap that did more than just that.

The night of Jan. 16, 1943, was a bitter cold one — around 10 degrees. It was cold enough that residents of the Laurelhurst neighborhood in southeast Portland were able to ice-skate on the shallow pond there in the park. The brand-new 523-foot, 16,000-ton steam tanker S.S. Schenectady, which had just rolled out of the Kaiser shipyard in Portland a week or two before, was docked there on the river, building steam to put out to sea.

And then, around 11 p.m., with a crack that one bystander said actually shook the ground, the huge ship suddenly broke in half, folding like a jackknife. The bow and stern plunged down into the water and wedged into the muddy bottom of the lagoon, pushing the middle of the ship high into the air. And the 30 crew members, who had been preparing the big ship to cast off and head out to sea, surely thought they were about to die.

Luckily, the water beneath the dock was shallow — barely deep enough to float the ship, which drew up to 30 feet depending on its load. The crew members were easily able to get up on deck. In the rush to escape, the third mate hurt his ankle, but that was the only injury.

This being war time, suspicions naturally turned to sabotage. But authorities quickly ruled that out. Eventually it was determined that flaws in some of the steel used to build the ship had made it brittle, and the temperature differential between the 10-degree air and the 40-degree river water had been enough to start a crack, which had raced around the ship from one side to the other, splitting the big vessel in half.

Because of where the ship was, the repair was relatively simple. The ship was simply sunk the rest of the way, so that it rested entirely on the bottom of the shallow lagoon; this naturally forced the crack closed as the weight of the ship straightened her out. Then scabs were welded across the crack, and she was refloated, and limped back upriver to the shipyard. A few weeks later, good as new, she was heading out to sea with a load of gasoline to power the American war machine.

We can only imagine how apprehensive the sailors assigned to the Schenectady’s crew must have been as the big, freshly patched ship cleared the Columbia Bar and headed out into the deep blue sea. But they did have one consolation: They were headed for the Pacific Theater … so at least it would be nice and warm.

(Sources: Cottage Grove Sentinel: Jan. 13, 20 and 27, 1949; Feb. 17, 1949; Portland Morning Oregonian, Jan. 10, 17, 19 and 21-24, 1943; Murray, Charles. “Engineering Disasters: S.S. Schenectady, a Lesson in Brittle Fracture,” Design News magazine, March 5, 2015)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn2@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.