Lonely orphan grew up to be president

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, February 22, 2017

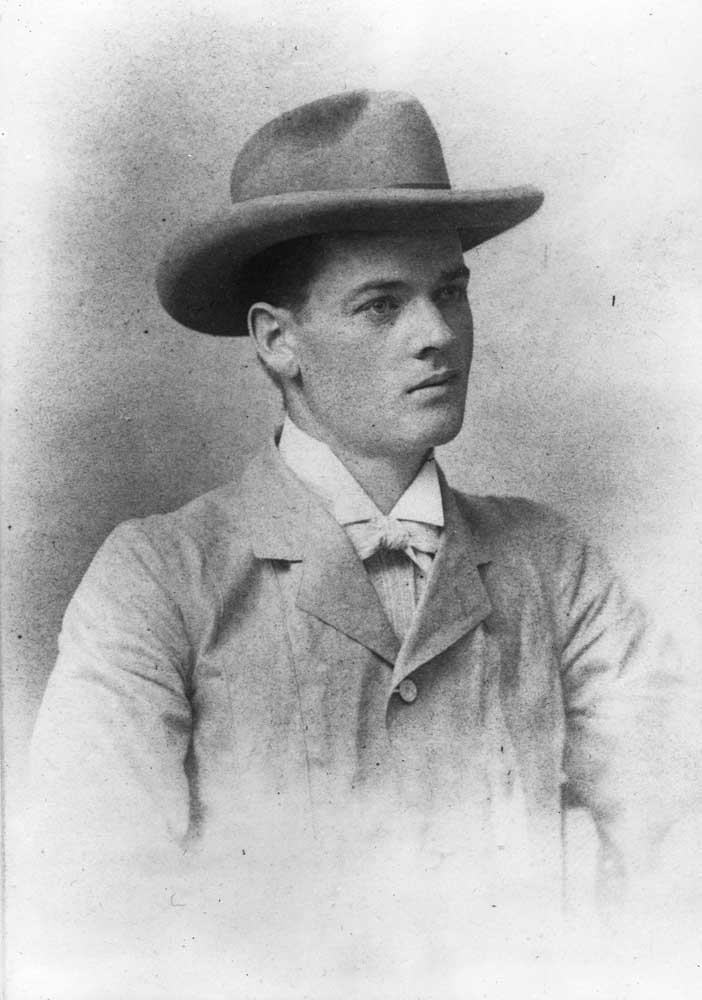

- Library of Congress / Submitted photoHerbert Hoover at age 23, when he was working as a gold mining engineer in Australia.

One wintery November day in 1885, a passenger train pulled into the depot in Newberg, and a lone little plain-dressed Quaker boy stepped off on the platform.

He was 10 years old, this boy, with a serious, unsmiling face and eyes that knew the deepest kind of grief. He looked just like a well-regimented orphan. Which, in fact, is exactly what he was.

This was young Bertie Hoover, just arrived from his home town of West Branch, Iowa. He’d been living there with an aunt for nine months after the death of his mother; his father, a blacksmith and inventor, he had lost already four years previously. Now he’d been sent all the way out to the Western edge of the continent to stay with his uncle John Minthorn, a physician and land developer in Newberg.

Bertie Hoover would spend most of his teenage years in Oregon, before leaving for college at age 17. The roots he put down in the Beaver State in those half-dozen childhood years must not have been very deep; he never came back to live, although he remained a member of the Salem Friends (Quaker) Meetinghouse throughout his life.

But many of the people he knew when he was in Oregon would remember him for many years after he left. And most of them would vote for him — twice — for the office of President of the United States.

Herbert Clark Hoover, the 31st President of the United States, is the closest Oregon has to a native-son President. (Historian Kyle Janssen calls him “Oregon’s native stepson.”) He was also the first President born west of the Mississippi River, and his running mate, Native American Charles Curtis of the Kaw Tribe, was the first (and, so far, the only) nonwhite vice-president in American history.

And along the way to the Presidency, he saved hundreds of millions of people in war-ravaged Europe from starving to death, in the process essentially inventing modern industrial-scale humanitarian relief. He still holds the world record for the most people directly saved from death by starvation (although, depending on your definitions, fellow Iowan Norman Borlaug may have him beaten).

Hoover’s Oregon story started with that rainy winter of 1885, at his uncle’s house. Uncle John Minthorn believed in the therapeutic value of hard work and plenty of it, especially for little orphan boys who chronically feel sorry for themselves. Before arriving at the farm, Hoover was often referred to as “Poor little Bertie”; after a year or two of constant toil in the fields and in the school, he started calling himself Bert.

The school was, of course, the local Quaker institution: Friends Pacific Academy, known today as George Fox University. But when his young ward was 13, uncle John moved to Salem and opened the Oregon Land Company, and Bert went with him, taking on a new role as office assistant. Essentially, he dropped out of high school to do this.

For the subsequent four years, Bert helped with the real-estate business, picking clients up at the railroad station in a wagon and chauffeuring them about to view property, keeping the books, and typing up documents.

In the spring of 1891, at the age of 17, Bert was looking around for colleges. Although he’d been out of high school since age 13, he’d taken night-school courses and probably done some home-schooling with his uncle. Everyone assumed he would go back east to some nice Quaker liberal-arts college — Earlham, perhaps, or Guilford.

But then a real-estate client told him about the new university being endowed by Leland Stanford in memory of his son. Impressed by the vision, Bert set his heart on being a member of Stanford’s pioneer class. And although his academic preparation turned out to be woefully inadequate, he spent the entire summer studying at Palo Alto, squeaked past the entrance exams and got in.

He’d never return to Oregon. Graduating three years later with a degree in geology at the height of a terrible recession, Hoover got a menial bottom-level job pushing an ore cart in a mine. From that lowly gig, over the subsequent two decades, he worked his way up to become one of the preeminent mining engineers in the world.

By 1914, Hoover was running a lucrative consulting firm and managing mining investments on all the continents; he and his wife, fellow Stanford alumna Lou Henry Hoover, had circumnavigated the globe at least half a dozen times and been under fire together during the Boxer Rebellion in China. Now in their early 40s, they were contemplating a sort of semi-retirement, and had even investigated the possibility of buying the Sacramento Union newspaper.

But all Hoover’s life plans, and much of his fortune, went up in smoke on one fateful August day when the Imperial German army invaded the neutral nation of Belgium, starting the First World War.

It would be the First World War, even more than the Presidency, that would really define Hoover’s life and contributions to the world. And his adopted home state of Oregon would have a role to play in helping him with that work — the challenge of keeping an entire nation fed despite the best efforts of two belligerent foreign powers, whose leaders thought starvation riots there would serve their war aims.

We’ll talk about how that came to be in next week’s column.

(Sources: Hoover Presidential Library and Museum at http://hoover.archives.gov; Hoover, Herbert. The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure, 1874-1920. New York: MacMillan, 1951; Nash, George. The Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, 1914-1917. New York: Norton, 1984)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn2@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.