For Milwaukie gas station owner, buying bomber was

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, February 10, 2016

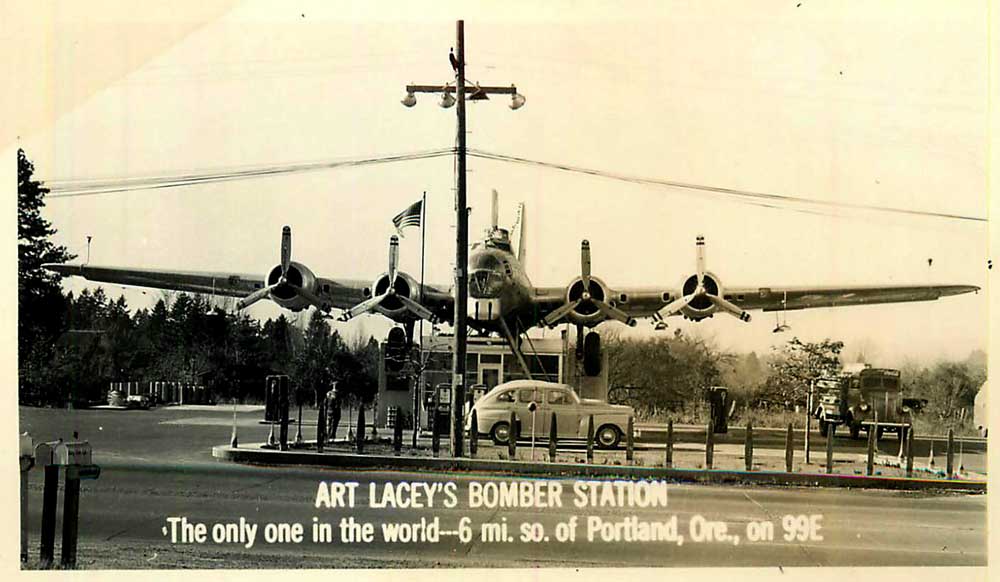

- Postcard / Submitted PhotoORIGThe Bomber as it appeared just a few years after Art Lacey installed its signature airplane in 1947.

It was the summer of 1947, and Art Lacey was in serious trouble.

He was about 50 feet above an Oklahoma airfield, at the controls of the biggest airplane he’d ever flown — a four-engine B-17G Flying Fortress, one of hundreds of the heavy bombers that the government was selling as surplus in the wake of the Second World War. This one was his; he had just bought it for $13,000. But now the landing gear was stuck in the retracted position, and it looked like he was about to crash it.

This wouldn’t have been such a big deal if it weren’t for his “copilot.” Lacey, not wanting to bother with getting someone to tag along with him, had brought a dressmaker’s mannequin borrowed from a friend, dressed it in flight gear and propped up in the seat, to fool the airfield manager into thinking there were two guys in the cockpit. After crashing the plane and ‘fessing up to this bit of deception, Lacey knew he would be in a less-than-optimal bargaining position vis-à-vis the defect in the plane he’d bought.

Still, that was all in the future. For now, the No. 1 goal was to not die in a giant fireball following a botched attempt at a gear-up landing. He lined the plane up as best he could with the runway and prepared to do his best.

Lacey’s whole crazy scheme had its genesis when he first learned about the surplus B-17s. They were super-cheap, selling for not much above their scrap value, because there just weren’t very many practical civilian uses for an obsolete heavy bomber. Lacey, already a successful Milwaukie businessman, had started stewing over how he might take advantage of the low prices on the big warbirds.

The more he thought about it, the cooler he thought it would look to have one of them perched above the gas pumps at his gas station on McLoughlin Boulevard. The wings could serve as a roof over the pumps, and there would be room for a lot of them. And best of all, it wouldn’t cost that much more than a stick-built structure of similar size.

According to Lacey’s daughter, Punky Scott, in an interview with KATU-TV Channel 2 News, the scheme he developed remained just a scheme until someone put money on the line. At his birthday party, he shared his vision of a “Bomber Gas Station” with a friend, who laughingly told him he was dreaming. Lacey promptly put up a $5 bet, which was just as promptly accepted, and just like that the whole crazy dream was turned into a serious plan.

Lacey immediately turned to a friend who, Scott suggested, was well connected with the dark side of Portland business — untaxed liquor, gambling, pinball machines, that sort of thing. “Got any money on you?” he asked. “I need $15,000.”

“And the guy had it on him,” Scott said in her interview. “I don’t know how that translates into today’s money, but it’s got to be a lot.”

It is. $15,000 in 1947 is the equivalent of $160,000 today — a pretty impressive wad for “walking-around money.”

Loaded down with this borrowed loot, Lacey made the journey to Oklahoma to buy his B-17. He had $13,000 for the plane and $2,000 for fuel and miscellaneous expenses on the way back.

Trouble started immediately upon arrival. After selling him the plane, the manager told him to bring his copilot the following day and he’d have the bird gassed up and ready. But Lacey hadn’t realized he’d need a copilot, so he hadn’t brought one.

He also hadn’t given much thought to the fact that he’d never flown a four-engine bomber in his life. He was a skilled private pilot of single-engine planes, but this was very different.

Still, Lacey was determined to have his plane. So he returned the next day with the borrowed mannequin, strapped it into the copilot’s seat, breezed into the manager’s office and walked out ready to fly home.

Hoping to familiarize himself with the big aircraft a bit before he started flying it for real, he started out with a few passes, touch-and-gos, and gentle turns — the yoke in one hand and the flight manual in the other. And it was going pretty well, he thought. But then he realized that the landing gear was stuck.

He flew the plane around for a while, trying to figure out how to get it unstuck. Finally he realized he’d just have to bring the plane in on its belly and hope for the best.

So down came Art Lacey in his new, doomed warbird, landing in a shower of sparks with a screech of tearing metal.

Although the cat was now out of the bag, the manager felt bad about the broken landing gear — and probably a little relieved, too, since his customer wasn’t dead.

“He turned to his secretary and said, ‘Have you written up the bill of sale yet on that B-17?’” Scott recounted. “And she said no, and he said, ‘Worst case of wind damage I’ve ever seen.’ And so he sold him a second B-17.”

The second plane set Lacey back just $1,500 — a special deal the manager made him, knowing he’d spent all his money on the first one.

Of course, faking the copilot was no longer going to work, so Lacey called his wife long-distance and asked her to send two of his friends down with a case of whiskey. The booze was to be used to bribe the local fire department to pump the fuel out of the old B-17 and into the new one using their fire truck, and it was a powerful enticement; Oklahoma was still a dry state at the time.

Everything worked as planned, although Lacey had to kite a check in Palm Springs, California, to refuel the big plane; luckily, he made it home to cover his paper before it could bounce.

But when he got home, Lacey found his troubles had just begun. The city of Portland wouldn’t issue permits to bring the plane from the airport. It was just too big, even after the wings were dismantled.

But Lacey was in so deep now, there was no turning back. He scheduled the move for the dark of night, well after the bars had all closed. He hired two teenagers with hot cars to accompany the motorcade, with instructions to floor it and race off recklessly into the night if the police should appear — the idea being to draw the cops away from the plane. The truck drivers were instructed that under no circumstances were they to stop before they arrived at the gas station, no matter who ordered them to. And he promised to pay any tickets anyone was written by any cop for his or her part in the move.

The move’s only mishap was a drunk driver who, seeing an airplane bearing down on him, thought he’d accidentally driven out onto an airfield and panicked and skidded into the ditch.

City Hall officials were, of course, furious. But after their initial attempts to punish Lacey resulted in some very unflattering newspaper coverage, they gave it up, fined him $10, declared victory and went home.

Lacey was able to pay half his fine with the $5 collected from his friend. He promptly had his airplane mounted above the gas pumps and renamed the place “The Bomber.” And there it sat for the next 63 years, bringing in hundreds of thousands of curious gawkers and customers alike.

Over the years the Laceys added a restaurant and a small hotel. In the early 1990s they closed the gas pumps, and the big B-17 started to look increasingly forlorn up there, exposed to the weather and the occasional predations of vandals.

Then, in 1996, the family decided to do something about it — and the B-17 Alliance was born, dedicated to restoring the “Lacey Lady,” as they’ve dubbed the bomber.

Currently the bomber is in the B-17 Alliance Museum and Restoration, located at McNary Airfield in Salem (3278 25th St. SE). The museum is open Fridays through Sundays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. The multimillion-dollar restoration still has a ways to go before it’s successfully completed, and the Alliance is working to raise the necessary funds to get it done; when it is, the Lacey Lady will be one of just seven B-17s remaining in flyable condition. Full details of the project are available at www.b71alliancegroup.com.

(Sources: “The Art Lacey Story,” www.b17alliancegroup.com; Bamesberger, Michael. “The ‘Lacey Lady’ B-17 bomber, a Milwaukie landmark, comes down from its perch,” Oregonian, Aug. 13, 2014; Spitaleri, Ellen. “Lacey Lady’s New Home,” Portland Tribune, Nov. 10, 2014)

Finn J.D. John teaches at Oregon State University and writes about odd tidbits of Oregon history. For details, see http://finnjohn.com. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn2@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.